Meet the forgotten enslaved and working-class labourers behind British exploration in Africa, Asia and Antarctica

By July 1858, the English explorer John Hanning Speke had been in Africa for 18 months. His eyes and body were weakened by fever, and he still hadn’t found what he set out to discover – the source of the River Nile.

Squinting through the heat on July 30, however, he spotted a body of water, about four miles away, surrounded by grass and jungle. At first, he could see only a small creek, flanked by lush fertile land used for growing crops and grazing by local people. But he pressed onward, dragging a reluctant donkey through jungle and over dried-up streams.

It wasn’t until August 3 that he could comprehend the full size of the lake. After winding up a gradual hill near Mwanza, located in the north of modern-day Tanzania, Speke was finally able to see a “vast expanse” of “pale-blue” water. He gazed on the lake’s islands and could see the outline of hills in the distance. Speke was arrested by the “peaceful beauty” of the scene. At the same time he was excited – he was convinced that this lake was what he’d been looking for. He was right. The Nile is the lake’s only outlet, and the huge body of water – now known as Lake Victoria – is the world’s second-largest freshwater lake.

Lack of time and money prevented Speke from travelling any further, so he came to understand the lake’s size by speaking to local people. As he didn’t speak any African languages, such conversations had to be translated multiple times. Thankfully, he had Sidi Mubarak Bombay to help him, a key figure in the expedition, who spoke both Hindi (which Speke could understand) and Swahili.

Despite another multi-year expedition from Zanzibar travelling inland to the area, in his own lifetime, Speke struggled to prove his claims. That’s because he only saw part of the lake and was unable to follow the river that flowed out of it the whole way to the coast. He died in 1864 from self-inflicted wounds sustained during a strange shooting incident, shortly before speaking at a debate about the source of the Nile.

But at least he is remembered by history. Bombay and the hundreds of African men and women who made his journey possible have since been largely forgotten. Such people did most of the hard work of exploration, building camps, navigating, cooking food and caring for Speke when he was sick.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

They are not the only ones. As a researcher specialising in the history of geography, I’ve spent almost eight years examining Victorian and Edwardian exploration and learned about the lives and experiences of African and Asian explorers, including Bombay. They included men and women who were formerly enslaved and were either forced into the work, or paid a pittance. Some of the women were forced into sexual relationships and marriages. Many were killed or badly injured in floggings at the hands of their brutal “masters” keen to administer punishment for perceived transgressions.

Their names should be in the pantheon of exploration, but all too often they are either ignored or misrepresented within the historical record. These are just some of their stories.

Speke and Bombay

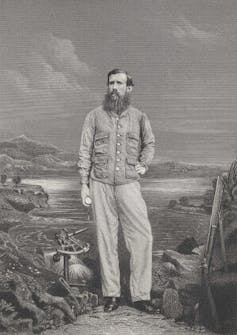

The portrait of Speke, circa 1893.

Royal Museums Greenwich

The illness and suffering Speke endured left a lasting mark on his body. Though he claimed to have fully recovered, his fellow British explorer on the expedition, the eccentric Richard F. Burton, argued in his book The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860) that Speke had sustained brain damage from sun stroke. In reality, he might have been showing the after effects of malaria and hearing loss. At one stage, a beetle had crawled into his ear, leaving him deaf for a month.

Even so, Speke led a further expedition to Africa to try to prove once and for all that he had “discovered” the source of the Nile.

He also published two books on his journeys. In the front of one, he used an etching of himself (based on a painting) standing before Lake Victoria. A copy of this painting still hangs in the headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society in South Kensington, London.

The image depicts Speke as a heroic and masculine figure. What we don’t see are the men and women who did the hard work of bringing Speke to the lake in the first place.

Sidi Mubarak Bombay was one of the most important figures within Speke’s expeditions. From Speke’s book about the expedition, which included a short biography of Bombay, we know he was born in 1820 near the modern border of Tanzania and Mozambique. His mother died when he was young, yet he remembered life in his village as one of “happy contentment” until, at the age of 12, when he was captured and enslaved by Swahili-speaking merchants.

He was then marched to the coast in chains before being sold at a slave market in Zanzibar. The man who bought him then transported him to India. Eventually, his owner died, and Bombay was freed. He returned to East Africa and enlisted in the Sultan of Zanzibar’s army. There, he met Speke and joined the East African Expedition in February 1857 and was paid five silver dollars a month.

The appointment changed Bombay’s life. The expedition was led by Burton, who had become famous for travelling to Mecca and Medina disguised as a Muslim pilgrim. Bombay became a key member of the expeditionary party.

Not only did he translate both Burton and Speke’s orders, but he also negotiated with local leaders for food, shelter and safe passage through their territory and cared for the explorers when they were sick. Bombay developed an active interest in the expedition’s work. In his book, Speke wrote that “by long practice, he has become a great geographer”.

When Speke returned to Zanzibar in 1860 for his next expedition, Bombay was one of the first men he recruited. He stayed with the expedition on its multi-year journey from Zanzibar to Cairo. Bombay went on to work for other European explorers, including Henry Morton Stanley who searched for the “lost” explorer David Livingstone, and Verney Lovett Cameron, who sought to investigate the lakes and rivers of Africa.

With Lovett Cameron, Bombay crossed equatorial Africa from coast to coast, completing much of the journey on foot. Even Victorian geographers recognised Bombay’s contribution, and he eventually received an award and pension from the Royal Geographical Society.

Anonymous labour and explorers’ violence

Bombay was a remarkable man. But Speke’s explorations also depended on many people we know far less about.

Both of Speke’s journeys to Lake Victoria were huge undertakings, involving hundreds of people. Much of the hard work was carried out by Nyamwezi porters from the central region of modern-day Tanzania. These men often worked on the pre-existing trade routes that connected the lake regions to the east African coast.

They carried the explorers’ supplies, basic equipment, trade goods and food. Explorers’ accounts often describe these people in racially offensive ways. Even so, their private letters also show their reliance on them.

An image from Speke’s book Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, illustrated by James Grant, showing ‘Speke’s faithfuls’.

Wiki Commons

On his journey to Lake Victoria, Speke struggled to recruit enough porters and complained: “I cannot move independently of the natives, and now the natives are not to be got for love or money [sic]. This alone has detained me here four whole months doing nothing.”

Alongside the porters, Speke also employed Swahili-speaking men from Zanzibar. These men often had their origins in East Africa and had often been enslaved in childhood. In his published account, Speke portrayed them in terms that drew on colonial tropes about childlike Africans.

In one letter to the British consul in Zanzibar, sent on December 12 1860, he was more positive, saying that such men do “all the work and do it as an enlightened and disciplined people”. These contrasting assessments perhaps reflect Speke’s varying mood. However, the different way he wrote in public might also be part of an effort to emphasise the difficulty of the journey and his leadership qualities.

Yet explorers sometimes struggled to maintain control over the parties they led. One problem was the fact that, once away from the coast and the power of the Zanazibari state, expedition members could easily slip away. Understandably, porters were more likely to leave an expedition when conditions became bad and food scarce.

Violent punishments were also a common feature of expeditions in this region. The explorers did not invent them – such punishments were also used by Arabic or Swahili-speaking merchants travelling in the area – but they showed little hesitation in using them. In his book on their 1856-59 expedition, Burton boasted that the expedition’s porters referred to him as “the wicked white man”.

Porters referred to Richard F. Burton as ‘the wicked white man’.

Hulton Archive

On Speke’s second expedition to Lake Victoria, his Scottish companion Grant described how one man “roared for mercy” when he was flogged 150 times after stealing cloth to buy food. In a letter to the Royal Geographical Society on February 17 1861, Speke wrote that this was the maximum number of lashes he would give out “for fear of mortal consequences”.

Later expeditions, such as those led by the Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley were even more violent.

During the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1887-89), Stanley decided to divide the party, leaving a “rear column” behind. Conditions in this group soon deteriorated, due to food shortages and disease. The column’s leader, the explorer Major Edmund Bartlott, carried out a string of violent punishments. One Sudanese porter was executed, while a Zanzibari man was flogged so many times that he died of the injuries.

Bartlott was only stopped from carrying out further acts of violence when he was killed by an African man fearful that he was about to attack his wife.

Women and girls on African expeditions

When Speke’s final expedition arrived in Cairo in 1863, having travelled from Zanzibar, the party also contained four young women who were photographed there. Their presence shows that African women often formed part of explorers’ expeditionary parties.

Sometimes the women joined voluntarily, often as the partners of porters. Others were enslaved women and girls purchased by other expedition members. One of the girls photographed in Cairo was named Kahala. Along with an older girl named Meri, she had been “given” to Speke by the queen mother of the African Kingdom of Buganda during Speke’s extended stay in the country.

Women and girls in Speke’s party in Cairo, from his Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, 1863.

CC BY-SA

Speke’s relationship with Meri took a remarkable turn. In an unpublished draft of his book, now held at the National Library of Scotland, he described her as “18 years or so” and “in the prime of youth and beauty”.

The manuscript also implies that their relationship had a sexual dimension, although it’s unclear if this was consensual. On April 12 1862, Speke claimed that he spent the night “taming the silent shrew” – alluding to a play by William Shakespeare in which a husband torments his strong-willed wife into submission. Even in his highly edited published account, Speke described himself as a “henpecked husband”.

His account then described the breakdown of their relationship in early May 1862. The breakup, Speke wrote in the unpublished draft of his book, “nearly drove my judgement from me” and left him with a “nearly broken … heart.” After this, Meri apparently showed “neither love, nor attachment for me”, suggesting she had shown some before this.

Speke eventually “gave” the younger girl, Kahala, to Bomaby because “she preferred playing with dirty little children to behaving like a young lady”. At first, Kahala was unhappy about this transfer and tried to run away. But she was soon found and returned to the party. She then stayed with the expedition to Cairo and travelled with Bombay when he returned to Zanzibar.

It was not unusual for women to try to join expeditionary parties. Explorers often had concerns about the presence of unmarried women within their ranks. For instance, in his book To The Central African Lakes and Back (1881) Joseph Thomson, who led an expedition to the Lake Regions of central Africa between 1878 and 1880, reported finding a woman in the expedition’s camp who was trying to reach the coast.

On the advice of the expedition’s experienced African headman James Chuma (who, like Bombay, became involved in multiple expeditions), Thomson forced the woman to marry one of the expedition’s porters. The woman does not seem to have been happy with this arrangement. While she stayed with the expedition for a while, she slipped away when they neared the coast.

James Chuma (left) with his colleague Abdullah Susi.

USC Digital Library

We only know the names of a small fraction of the women involved in such expeditions. Grant wrote a book on their journey that gives further details about women in the party.

In it he noted that several of the porters travelled alongside female partners who were “generally carrying a child each on their backs, a small stool … on their heads, and inveterately smoking during the march. They would prepare some savoury dish of herbs for their men on getting into camp, where they lived in bell-shaped erections made with boughs of trees”.

Such passages give us only a tantalising glimpse of these women. We’re left without a detailed knowledge of their names or lives. But we do know that they contributed to these expeditions in important ways.

Isabella Bird and Ito

More well known are the stories of the growing number of British women who became explorers in the Victorian era. Foremost among them was Isabella Bird.

Isabella Bird wearing Manchurian clothing from a journey through China.

New York Public Library

Born in 1831 to an upper-middle class family and less than 5ft tall, Bird did not begin her career as an explorer until middle age. She was also disabled. At the age of 18, Bird had a “fibrous tumour” removed from the base of her spine and afterwards lived with chronic back pain. She travelled, often on horseback, to every continent of the world except Antarctica. Bird was also one of the first women admitted to the then all-male Royal Geographical Society in 1892.

Bird’s gender and disability shaped how she travelled. Unable to walk for long distances, she often rode cross-saddle, rather than the more traditionally feminine side-saddle, which she found painful. In some places, she faced specific hostility because she was a woman.

Yet, in other ways, Bird’s journeys had shared similarities with those made by men. Like them, she often depended on local people during her journeys. When she travelled through Japan in 1878, she relied on the services of an 18-year-old Japanese man named Itō Tsurukichi. He played a vital role in her journey across the country, arranging much of her travel, translating conversation with local people and explaining what she was looking at.

In Bird’s published accounts, her descriptions of Tsurukichi are often laced with racial prejudice. She often referred to him as a “boy” and was disparaging about his physical appearance. Her perspective on him did soften a little, however, as their journey continued. She was impressed by his qualities as a translator and the fact that he was continually trying to improve his linguistic skills.

Tsurukichi’s essential role was also illustrated when Bird attended a Japanese wedding to which he was not invited. She complained that it was like being “deprived of the use of one of her senses”.

Bird’s account also raises questions of who the leader of their journey through Japan was. “I am trying to manage him, because I saw that he meant to manage me,” she wrote in her book Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (1880). Bird also reported an incident where a Japanese boy thought “that Ito was a monkey-player, ie. the keeper of a monkey theatre, I a big ape, and the poles of my bed the scaffolding of the stage!”

Itō Tsurukichi.

National Diet Library

Bird viewed the child’s misunderstanding as amusing, but it does suggest that some outsiders thought Tsurukichi was leading the party. He was clearly a skilled guide and translator, and he went on to become one of the foremost tour guides in Japan, taking numerous western travellers around the country.

Like Burton and Speke, Bird often depended on guides on her journeys. Sometimes, she led much larger groups. In such situations, others cooked her food, packed her tent, and translated conversations with local people.

When she travelled in China in the 1890s, Bird was carried across much of the country in an open chair on the shoulders of three separate groups of chair-bearers. She often didn’t record the names of the men who did such work and only described their labour in quite general terms – though she did photograph some of them and her chair.

However little men like Bombay and Tsurukichi are remembered, it is at least possible to recover their names.

Scott and Antarctica – exploration in an unpopulated land

In the early 20th century, the exploration of Antarctica was a thoroughly masculine affair. Some women did apply to join Antarctic expeditions, such as those led by Ernest Shackleton, but their applications were turned down. Antarctic expeditions were also less ethnically diverse than those in the Arctic. In the north, explorers often relied on the skills and labour of Indigenous people. There were also Black explorers, including Matthew Henson, an African-American man who claimed to be one of the first men to stand on the North Pole.

Antarctica presented a unique challenge: it is unpopulated, and when British explorers made their first attempts to explore its interior in the early 20th century, they had no idea what to expect.

In contrast to diverse expeditions elsewhere in the world, Antarctic expeditions were comparatively homogenous undertakings. British expeditions, led by Robert Falcon Scott and Shackleton, mostly employed white men from within the British empire. Sledging journeys in Antarctica were quite egalitarian compared with expeditions in Africa and Asia. Sledging often required upper and middle-class officers and scientists to work collaboratively with working class sailors, who often pulled sledges forward by sheer force of muscle.

Shackleton, Scott and Edward Wilson before their march south during the Discovery expedition in 1902. Sledges visible in the background.

National Library of New Zealand

On the British National Antarctic Expedition, Scott completed a long sledge journey to the Polar Plateau with stoker William Lashly and petty officer Edgar Evans. The men cooked, ate, slept and laboured together. Scott, an officer, found the experience revealing, learning much about the working-class men’s experiences in the Royal Navy. Antarctic explorers were more willing to acknowledge the manual labour that made their expeditions possible than Burton, Speke or Bird, partly because this work was done by white men.

Some working-class sailors – such as Edgar Evans, Tom Crean, or William Lashly – did achieve a certain degree of celebrity. But others figures are overlooked. On Scott’s expedition he employed two men from within the Russian empire to help care for and train the expedition’s ponies and huskies: Dmitrii Girev and Anton Omelchenko. Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the expedition’s assistant zoologist, noted that they “were brought originally to look after the ponies and dogs on their way from Siberia to New Zealand. But they proved such good fellows and so useful that we were very glad to take them on the strength of the landing party”.

Girev, from the far east of Russia specialised in looking after the expedition’s Siberian huskies, while Omelchenko, born in Ukraine, specialised in caring for the ponies who would haul Scott’s supplies towards the South Pole. They therefore played a vital role in the expedition. In their accounts, Scott and Cherry-Garrard referred to these adult men using the infantilising term “boys” – thereby stripping them of their status as full and equal members of the expeditionary party.

Even among the British expedition members, there were still significant disparities in how labour on polar expeditions was rewarded or reported. Working-class men, mostly sailors drawn from the Royal Navy, did much of the hard, unglamorous work. They were also paid much less than officers and scientists.

On Scott’s two Antarctic expeditions, much of the day-to-day work at base camp – such as cooking, cleaning, and collecting ice to melt into drinking water – was carried out by working-class sailors.

On his final expedition, the explorers spent the winter in a small hut on Ross Island. One man, Thomas Clissold, worked as the expedition’s cook. Frederick Hooper, a steward who joined the shore party, swept the floor in the morning, set the table, washed crockery and generally tidied things. “I think it is a good thing that in these matters the officers need not wait on themselves,” Scott commented in his diary. “It gives long unbroken days of scientific work and must, therefore, be an economy of brain in the long run.”

Thomas Clissold making bread during the the British Antarctic expedition of 1911-1913.

National Library of New Zealand, CC BY-NC

He had adopted a similar approach on his first expedition, which left some sailors frustrated. “We don’t have any idea of what has been done in the scientific work, as they don’t give us any information,” James Duncan, a Scottish shipwright on the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901-1904) complained in his diary. “It’s rather hard on the lower deck hands.”

Even memorials to Antarctic explorers perpetuate many of the heroic myths of exploration. If you walk around London today, you might stumble on the statue of Scott in Waterloo Place or one of Shackleton outside the headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society in South Kensington. Such statues embody much of what we often get wrong about exploration, depicting explorers as solitary. Expeditions were collective projects, and many of the people involved haven’t had their contributions fully recognised.

In many parts of the world, expeditions were large, diverse undertakings. Yet many of the people who did most of the work have been forgotten. My research seeks to put them in the spotlight and recover something of their lives and experiences.

Expeditions are extreme situations in which human bodies are pushed to (and sometimes beyond) their limits. Because of this, they vividly illustrate the various ways humans depend on each other – for care, food, shelter, transport and companionship. Today, human societies are more complex and interdependent than ever. Though often in less extreme or dramatic ways, like explorers, we all depend on other people for survival.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Edward Armston-Sheret has received funding from the Institute of Historical Research (via the Alan Pearsall Fellowship in Naval and Maritime History), the Royal Historical Society, The Royal Geographical Society, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (via the Techne Doctoral Training Partnership).