A brief history of the slogan T-shirt

You probably have a drawer full of T-shirts. They’re comfy, easy to style, cheap and ubiquitous. But the T-shirt is anything but basic. For 70 years, they’ve been worn as a tool for self-expression, rebellion and protest. And in 2025, the slogan T-shirt is as powerful as it has ever been.

Previously worn as an undergarment, the T-shirt became outerwear after the second world war. Snugly dressed on the bodies of physically fit young men, it came to signify heroism, youth and virility.

The T-shirt was adopted by sub-cultural groups such as bikers and custom car fanatics. And it was popularised by Hollywood stars, including Marlon Brando and James Dean. By the mid-1950s, it had become a symbol of rebellion and cool.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

From the 1960s onwards, slogan T-shirts gained momentum in America and Britain, and women began wearing them as the fashions became more casual. In the postmodern era, language became less about function and more about individualistic expression and exploration. This playful approach to words, combined with an emphasis on design and social commentary, made the T-shirt an ideal canvas for the championing of individual thought.

Anti-war messaging dominated slogans in the US during the Vietnam war and amid the increasing threat of nuclear war. Perhaps the most recognised slogan featured the artwork from John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s famous 1969 “War is Over” campaign, a T-shirt which is still being replicated today. Messages of peace on clothing, whether featuring words or symbols, have stayed in our collective wardrobe ever since, from high fashion to high street.

In the 1970s, the New York Times called T-shirts the “the medium of the message”, and the message itself was becoming ever more subversive. Slogan tees sought to provoke, whether through humour or controversy.

Punks were especially good at it. They constructed what subculture theorist Dick Hebdige called a “guttersnipe rhetoric” in his 1979 study Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Designers Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren paved the way for a DIY approach where slogans were often scrawled, expressive and upended social codes.

The slogan shirt in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights

Manufacturing and printing advancements in the postmodern era also meant that more designs could be printed en masse – a development used by the LGBTQ+ community and its allies.

Some of the most memorable slogan T-shirts in history were created in response to the Aids epidemic in the 1980s. The most poignant simply read “Silence = Death”. Originally a poster, the design was printed on T-shirts by the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (known as “Act Up”) for protesters to wear.

Those affected by Aids were demonised and largely ignored, so the queer community was reliant on activism to incite action from government and their fellow citizens.

In After Silence: A History of Aids through Its Images (2018), author Avram Finkelstein describes the grassroots activism of the time as an “act of call and response, a request for participation” for the lives at stake. In a pre-internet world, T-shirts provided a platform to make the fight visible.

The 80s also saw slogan T-shirts enter pop cultural spaces as well as political ones, most notably with designs from Katharine Hamnett. Known for their oversized fit, their politically charged messages adorned the torsos of celebrities including George Michael and Debbie Harry. In 1984, Hamnett made fashion history when she met then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher while wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with “58% Don’t Want Pershing”, referencing her anti-nuclear sentiment.

That same year, Hamnett’s “Choose Life” design gained icon status when it was worn in a music video by Wham!. Originally a reference to the central teachings of Buddhism, “Choose Life” took on complex meaning when read in the context of the Aids epidemic, Thatcherism and economic instability.

The Choose Life shirt featured in Wham!‘s video for Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go.

The slogan was later used in the opening monologue of the cult film Trainspotting (1996), which is set in an impoverished and drug-fuelled Edinburgh. The design has been reworked countless times, including by Hamnett herself for the refugee charity Choose Love.

In author Stephanie Talbot’s 2013 book Slogan T-shirts: Cult and Culture, she explains that slogan tees can move through time to achieve iconic status. While the Choose Life tee has transcended time and generations, it also shows how the intended message of a slogan can change depending on the wearer and the observer, and the environment within which it’s worn.

Today, to Hamnett’s consternation, Choose Life has been co-opted by pro-life campaigners, not only taking on a different meaning but flipping across the political spectrum.

Who gets to wear a slogan shirt?

When we wear a slogan T-shirt, we are transferring our internal self to an external, public self, creating an extension of ourselves that invites others to perceive us. This creates opportunities for conflict as well as connection and community, putting our bodies (particularly those that are marginalised) at risk.

In 2023 for example, numerous peaceful protesters were arrested for wearing Just Stop Oil T-shirts, highlighting how unsafe – and potentially unlawful – it can be to wear a slogan T-shirt.

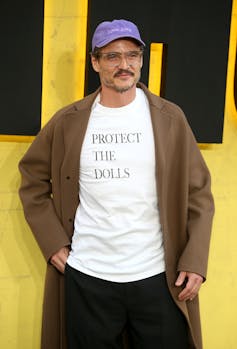

Actor Pedro Pascal wears the ‘Protect the Dolls’ shirt by Connor Ives.

Fred Duval/Shutterstock

However, the LGBTQ+ community is continuing to seize the power of the slogan T-shirt – not in spite of law changes, but because of them.

Designer Connor Ives closed his 2025 London Fashion Week show wearing a T-shirt that read “Protect the Dolls”, during a time of increasing politicisation of trans lives and gender healthcare. The term “dolls” is one of endearment in queer spaces that refers to those who identify as feminine, including trans women.

After receiving a “groundswell” of support, the T-shirt went into production to raise money for American charity Trans Lifeline. Numerous celebrities have since worn the design, including actor Pedro Pascal and musician Troye Sivan, to show their support in the face of multiple law changes.

In a world that increasingly feels like it’s in turmoil, for many, the humble T-shirt still feels like a space where we can express how we truly feel.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Liv Auckland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.