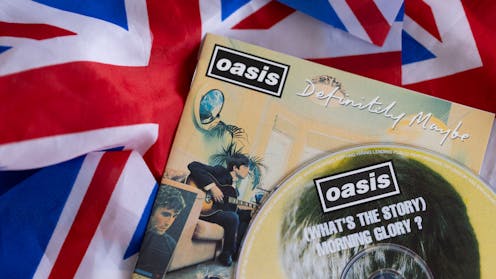

Will the Oasis reunion usher in a Britpop summer – or is it just a marketing ploy?

The trend for naming summers has become something of a cultural phenomenon. Think for example of 2019, which was branded a “hot girl summer”, inspired by rapper Megan Thee Stallion’s song.

In 2021 there was the much-ridiculed “white boy summer” (named after a song of the same name by Tom Hanks’s son, Chet). Then 2022 was “feral girl summer” and 2024, of course, was a “brat summer”, after Charli XCX’s cultural phenomenon album Brat.

And this summer? Well, with the likes of Oasis, Pulp, Supergrass, Suede, Shed Seven and Cast all playing UK dates between June and August, it’s “Britpop summer”, of course. The question is, though, whether these names are actually (and accurately) representing the zeitgeist, or if they are just the result of savvy marketing strategies.

Such things may now be occurring more frequently, but they’re nothing new. The year 1967 was famously coined “the summer of love”, a moniker supposedly invented by the Californian local government to put a positive spin on the druggy, hairy, hippy gatherings taking place across the state.

Then, just over two decades later, there came the imaginatively titled “second summer of love” in 1988 which, like its predecessor was drug-inspired, but this time involved British ravers taking ecstasy in London warehouses instead of hippies “dropping acid” in San Franciscan parks.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The “summer of love” has largely been presented to us as a psychedelic utopia, wherein London was the “swinging, cool and hip” epicentre of a new cultural movement. Everyone was blissfully stoned, with messages of peace and love on their lips, kaftans and floral blouses on their bodies and flowers in their hair.

In reality, though, in the UK at least only 8% of adults had actually tried cannabis and fewer than 1% had taken LSD or acid, and the fashion of the day (for men, anyway) involved sensible slacks and short-back-and-sides.

Such un-psychedelic appetites also spilled over into mainstream music. Although it’s now the UK’s bestselling album ever, in 1967, The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was only the sixth-biggest album of the year in terms of sales. It was bested by the very suitably non-flower-power Herb Alpert, The Monkees and The Sound of Music soundtrack.

Pink Floyd’s debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – “the founding masterpiece in psychedelic music” – sold 275,000 copies in 1967 in the UK (compared to The Sound of Music’s 2.4 million) and was number 34 on the list of big-selling albums in the UK that year.

The same year, 1967, also saw the “best double-A side ever released”, The Beatles’ Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields Forever. It was kept off the number one spot by Engelbert Humperdinck’s Please Release Me.

Inside the so-called ‘second summer of love’.

It seems, then, that for most of the British public, it was less a “summer of love” and more a “summer of Humperdinck”. Fast-forward five decades, and we see the same kinds of things happening. The year 2019 was a “hot girl summer”, Megan Thee Stallion’s song only peaked at 40 in the UK singles charts and her gigs sold poorly.

Like our “summer of Humperdinck”, were such things based on popularity, we may have expected a “Sheeran summer”, with Ed Sheeran’s duet with Justin Bieber, I Don’t Care, dominating the charts and airwaves.

Similarly, although 2024 was a “brat summer”, Charli XCX’s album was actually only the UK’s eighth-biggest selling album of the year, with Taylor Swift’s very un-Brat-like The Tortured Poets Department achieving 783,820 sales – almost double Brat’s.

Read more:

Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department and the art of melodrama

Britpop summer

Britpop itself may have peaked in 1995, but in the summer of 1996, with Oasis and Blur still omnipresent, Tony Blair talking about the prospect of freedom, aspiration and ambition, England progressing through the Euros on home soil, and sunny day after sunny day, it was (according to The Guardian, at least) the most optimistic period in recent British history where anything seemed possible.

Pulp performed a secret set at Glastonbury 2025 to huge crowds.

We may all have become more cynical in the intervening years, but in the midst of another heatwave, with Pulp at Glastonbury, and the Gallaghers reunited, it does feel like there’s something in the air again.

Indeed, standing among tens of thousands of fellow music fans in the sweltering heat watching Jarvis Cocker strutting his gangly stuff, if I ignored the grey in his beard, the iPhones in the crowd, and the aching in my legs, it could have been the nineties all over again.

Britpop summer? I’m all for it. And maybe this will be one time that the name really does represent the nation’s mood.

Glenn Fosbraey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.