Parting by Sebastian Haffner: the forgotten German novel of the early 1930s that’s become a bestseller

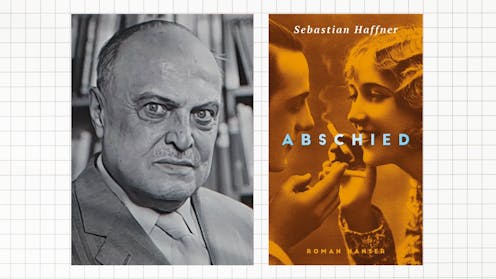

Sebastian Haffner and his novel, Abschied (Parting). Wiki Commons/Canva, CC BY

Abschied (Parting) by Sebastian Haffner (1907-1999) is dominating the bestseller charts in Germany. It has been published posthumously, over 25 years after his death, after the manuscript was found in a drawer.

The novel is a love story between Raimund, a young non-Jewish German student of law from Berlin, and Teddy, a young Jewish woman from Vienna. Raimund and Teddy meet on August 31 1930 in Berlin and the novel covers the time they spend in Berlin and Paris together.

Abschied was written between October 18 and November 23 1932, just before the Nazi takeover. It reads in the breathless, immediate manner in which it was clearly conceived. It also gives a personal insight into the zeitgeist of the final months of the Weimar Republic.

Haffner was born Raimund Pretzel in Berlin, where he trained as a lawyer. He disagreed with the Nazi regime and emigrated to London in 1938. There, in order to protect his family in Germany from potential Nazi retribution he changed his name.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

It is estimated that around 80,000 German-speaking refugees from Nazism lived in the UK by September 1939. Most of these refugees were Jewish, but there was also a sizeable number who, like Haffner, had fled for political reasons. Many politically committed exiles arrived soon after 1933 but this was not the case for Haffner. In the 1930s he was busy being a young man in Berlin, training as a lawyer and enjoying himself.

Haffner’s father was an educationalist who had a library with 10,000 volumes. As a young man Haffner liked reading, and toyed with the idea of becoming a writer and journalist, but his father advised him to study law and aim for a career in the civil service. Political developments in Germany made this option increasingly unpalatable. Initially Haffner found it difficult to see a way out. As he wrote in Defying Hitler: “Daily life […] made it difficult to see the situation clearly.”

In the book he also describes how he and other Germans acquiesced to the new regime. Haffner was disgusted with his own reaction to the SA (the Nazi party’s private army) entering the library of the court building where he was a pupil, asking those present whether they were Aryan and throwing out Jewish members of the court.

When questioned by an SA man, Haffner replied that he was indeed Aryan and felt immediately ashamed: “A moment too late I felt the shame, the defeat. I had said, ‘Yes’. […] What a humiliation to have answered the unjustified question whether I was Aryan so easily, even if the fact was of no importance to me.” Haffner never really took up his career as a lawyer, because it would have meant upholding Nazi laws and Nazi justice. Instead he started working as a journalist and writer, first in Germany and after his escape in 1938 in the UK.

Life in the UK

Soon after his arrival in the UK, Haffner finished a book titled Defying Hitler (1939). The memoir was both autobiographical and a political history of the period – but after the outbreak of the second world war it was considered not polemical enough, and was dismissed as an unsuitable explanation for the rise of Nazism at the time. But the intermingling of private and public history is of great interest to readers in the 21st century. Defying Hitler was published posthumously in German (2000) and in English (2003) and became a bestseller in both languages.

After Defying Hitler, Haffner turned to writing another book, Germany: Jekyll and Hyde (1940). It was more clearly anti-Nazi and focused on his journalism – during the war, he worked for the Foreign Office on anti-Nazi propaganda and he was later employed by The Observer as a political journalist. The book was a success, and Winston Churchill is said to have told his cabinet to read it.

The handwritten manuscript for Abschied, which was never published in Haffner’s lifetime, was found in a drawer by his son Oliver Pretzel, some time after his father’s death.

The German critic Volker Weidemann who wrote the epilogue to Parting toys with the idea that it was never published because its focus on the love story was considered a bit too trivial for such a great writer. Thanks to his work for The Observer after 1941, Haffner was a well-regarded political journalist and historical biographer. He became the paper’s German correspondent in 1954, and was well known for his column in West Germany’s Stern magazine and for his biographies, including one on Churchill (1967).

The perspective of a young non-Jewish German living a relatively ordinary life in the early 1930s makes Abschied a fascinating read. Academics have been exploring everyday life under Nazi rule for nearly half a century now, but it seems that modern readers are still keen to learn about it today.

Perhaps the novel resonates with so many German readers because we live in a time where many struggle with the inevitable continuation of everyday life while politics is becoming ever more extraordinary.

Andrea Hammel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.