Why snappy dogs, scratchy cats, and hungry worms were part of a medieval woman’s vision of the afterlife

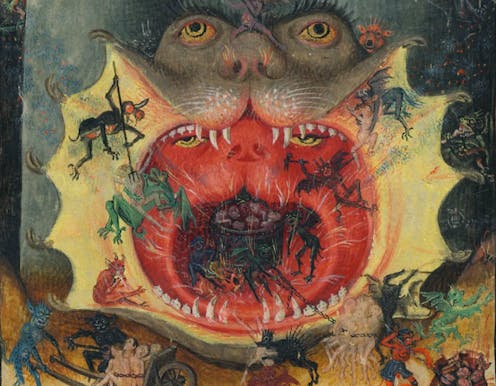

Detail from The Mouth of Hell in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves (1440). The Morgan Library & Museum

The afterlife is not typically associated with aggressive pets and insatiable worms. But these are exactly the creatures that appeared to an unnamed woman recluse living in Winchester, England, over the course of three nights in the summer of 1422. The woman was an anchoress. That means she had chosen – and subsequently vowed – to live in solitary confinement within a small cell attached to a church for the rest of her life.

The recluse wrote a vivid account of her vision and sent it to her confessor and a circle of influential churchmen. Her letter, known today as A Revelation of Purgatory, makes her one of the earliest known women writers in the English language.

Despite deserving this accolade, the Winchester recluse did not appear alongside her more famous contemporaries or near contemporaries, Julian of Norwich (1342 – after 1416) and Margery Kempe (circa 1373 – after 1438), in the British Library’s hugely successful recent exhibition, Medieval Women: In Their Own Words. One likely reason for this is that the manuscript copy of the full account of the vision was not available for display at the time. That situation has now changed.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The British Library has just announced the purchase of five medieval manuscripts from Longleat House in Wiltshire. One of these manuscripts contains the complete surviving version of the recluse’s letter, which, although referred to in an incomplete version elsewhere as “a revelation recently shown to a holy woman”, is untitled in this particular manuscript. This may be another reason for this woman’s writing having been overlooked until very recently. This exciting purchase will hopefully now give the Winchester recluse and her writing the attention they deserve.

Angels feeding souls through a purgatorial furnace in the 15th century manuscript Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

Wikimedia Commons

In her vivid, technicolor visions, the recluse watched a dead friend, a nun named Margaret, ushered to the forefront of purgatory by a cat and dog that she had adored and pampered when she was alive.

Transformed into vicious satanic minions, Margaret’s former pets joined the many devils responsible for doling out her punishments. They tore endlessly at her flesh and bit and scratched her relentlessly. They did so to remind her that, as a nun, she had broken her vows by keeping them as her companions in her nunnery and by devoting too much love and attention to them.

In Margaret’s heart, too, a voracious little worm had taken up residence – a so-called “worm of conscience” – that was intent on consuming her from the inside out as part of her torment.

Read more:

Cats in the middle ages: what medieval manuscripts teach us about our ancestors’ pets

So deeply troubling was this vision of her friend’s suffering that the Winchester recluse immediately summoned her young maid, and the two women started to pray for the nun’s soul. On the very next day the recluse decided there was nothing for it but to document her visions of Margaret’s fate. She not only detailed all she had seen, but also stipulated which prayers, and how many, should be said on behalf of poor Margaret to deliver her from her suffering and help her reach the gates of heaven.

The recluse’s letter is very specific about the date of these visions: they took place on St Lawrence’s day, August 10 1322, which fell on a Sunday that year. There was – and still is – a small church dedicated to this saint very close to the cathedral in Winchester (the so-called Mother Church of Winchester).

As an anchoress, the author would almost certainly have occupied a cell attached to a church somewhere in Winchester. This would also have allowed her the time and the space for contemplation, study and writing.

Read more:

Dogs in the middle ages: what medieval writing tells us about our ancestors’ pets

As has been argued in a recent blog and podcast for the University of Surrey’s Mapping Medieval Women Writers project, it is quite possible that the Church of St Lawrence was the location of her cell, where she experienced her visions, and where she wrote down her account of them.

This manuscript now permanently joins an unparalleled collection of medieval women’s writing in England held in the British Library. It includes not only The Book of Margery Kempe, manuscripts of both the short and long texts of Julian of Norwich’s Revelations, but also the Lais and Fables of Marie de France, the Boke of Saints Albans attributed to Juliana Berners, and the letters of the 15th-century Norfolk gentlewoman Margaret Paston and other female family members.

As such, the work of this unnamed Winchester anchoress now takes up its rightful place alongside the writing of her hitherto better-known literary sisters.

Diane Watt has received funding from the AHRC, British Academy and Leverhulme Trust.

Liz Herbert McAvoy received funding for an associated project from the Leverhulme Trust.

Amy Louise Morgan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.