China’s interest in the next Dalai Lama is also about control of Tibet’s water supply

As the 14th Dalai Lama celebrates his 90th birthday with thousands of Tibetan Buddhists, there’s already tension over how the next spiritual leader will be selected. Controversially, the Chinese government has suggested it wants more power over who is chosen.

Traditionally, Tibetan leaders and aides seek a young boy who is seen as the chosen reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. It is possible that after they do this, this time Beijing will try to appoint a rival figure.

However, the current Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in India, insists that the process of succession will be led by the Swiss-based Gaden Phodrang Trust, which manages his affairs. He said no one else had authority “to interfere in this matter” and that statement is being seen as a strong signal to China.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

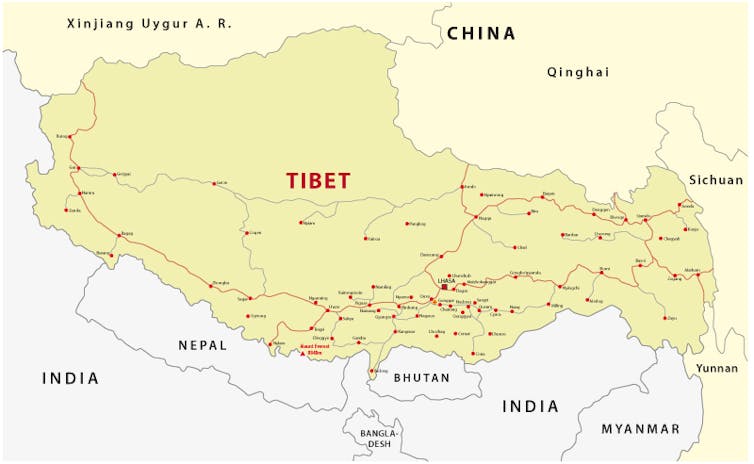

Throughout the 20th century, Tibetans struggled to create an independent state, as their homeland was fought over by Russia, the UK and China. In 1951, Tibetan leaders signed a treaty with China allowing a Chinese military presence on their land.

China established the Tibetan Autonomous Region in 1965, in name this means that Tibet is an autonomous region within China, but in effect it is tightly controlled. Tibet has a government in exile, based in India, that still wants Tibet to become an independent state.

This is a continuing source of tension between the two countries. India also claims part of Tibet as its own territory.

Beijing sees having more power over the selection of the Dalai Lama as an opportunity to stamp more authority on Tibet. Tibet’s strategic position and its resources are extremely valuable to China, and play a part in Beijing’s wider plans for regional dominance, and in its aim of pushing back against India, its powerful rival in south Asia.

The Dalai Lama celebrates his 90th birthday as many Tibetans living in China fear talking about independence.

Tibet provides China with a naturally defensive border with the rest of southern Asia, with its mountainous terrain providing a buffer against India. The brief Sino-Indian war of 1962 when the two countries battled for control of the region, still has implications for India and China today, where they continue to dispute border lands.

As with many powerful nations, China has always been concerned about threats, or rival power bases, within its neighbourhood. This is similar to how the US has used the Monroe Doctrine to ensure its dominance over Latin America, and how Russia seeks to maintain its influence over former Soviet states.

Beijing views western criticism of its control of Tibet as interference in its sphere of influence.

Read more:

India and Pakistan tension escalates with suspension of historic water treaty

Another source of contention is that Beijing traditionally views boundaries such as the McMahon line defining the China-India border as lacking legitimacy, a border drawn up when China was at its weakest in the 19th century. Known in China as the “century of humiliation”, this was characterised by a series of unequal treaties, which saw the loss of territory to stronger European powers.

This continues to a source of political tensions in China’s border regions including Tibet. This is a controversial part of China’s historical memory and continues to influence its ongoing relationship with the west.

Demand for natural resources

Tibet’s importance to Beijing also comes from its vast water resources. Access to more water is seen as increasingly important for China’s wider push towards self-sufficiency which has become imperative in the face of climate change. This also provides China with a significant geopolitical tool.

For instance, the Mekong River rises in Tibet and flows through China and along the borders of Myanamar and Laos and onward into Thailand and Cambodia. It is the third longest river in Asia, and is crucial for many of the economies of south-east Asia. It is estimated to sustain 60 million people.

China’s attempts to control water supplies, particularly through the building of huge dams in Tibet, has added to regional tensions. Around 50% of the flow to the Mekong was cut off for part of 2021, after a Chinese mega dam was built. This caused a lot of resentment from other countries which depended on the water.

Moves by other nations to control access to regional water supplies in recent years show how water is now becoming a negotiating tool. India attempted to cut off Pakistan’s water supply in 2025 as part of the conflict between the two. Control of Tibet allows China to pursue a similar strategy, which grants Beijing leverage in its dealings with New Delhi, and other governments.

Another natural resource is also a vital part of China’s planning. Tibet’s significant lithium deposits are crucial for Chinese supply chains, particularly for their use in the electric vehicle industry. Beijing is attempting to reduce its reliance on western firms and supplies, in the face of the present trade tensions between the US and China, and Donald Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods.

Tibet’s value to China is a reflection of wider changes in a world where water is increasingly playing an important role in geopolitics. With its valuable natural resources, China’s desire to control Tibet is not likely to decrease.

Tom Harper does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.