In Reframing Blackness, Alayo Akinkugbe challenges museums to see blackness first

In Reframing Blackness, writer and curator Alayo Akinkugbe explores the way that art history is taught, and the impact this has had on what we see in national museums in western cities. This teaching has often led to the exclusion of blackness from mainstream art spaces. Akinkugbe challenges this by shifting our gaze – to see blackness first.

Her book interrogates the place of blackness in relation to art history in several ways. First, she observes that the lack of black curators within national museums in western cities means that blackness is subject to “reactive responses”.

For example, when there was a global outcry after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, institutions reacted by foregrounding their efforts to support black artists and pledging commitments for future initiatives.

But many of these initiatives remain on the surface level and temporary, rather than permanently embedded into the institutional fabric. In my experience, long-term change is unlikely to occur when progress is measured by individual projects, while the decision-making remains in the same hands.

Next, the book draws on Akinkugbe’s experience as a history of art student at the University of Cambridge, during which time there was a call to “decolonise” the curriculum.

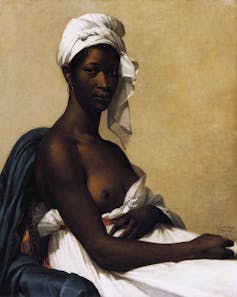

She then explores the intersection of race, gender and class, highlighting the double-bind of racial and gender bias that black women may encounter. She suggests ways to shift the gaze by focusing on people of colour depicted in historic artworks, including Portrait d’une Femme Noire (Portrait of a Black Woman) (1800) by Marie-Guillemine Benoist.

Along the way, we are acquainted with figures that have always been present on museum and gallery walls – albeit often ignored or faded into obscurity. Akinkugbe speculates about who some of these unnamed figures were, and what worlds they inhabited.

In Jacques Amans’ painting, Bélizaire and the Frey Children (1837), for example, Bélizaire, a black enslaved child, was over time painted over and faded into the background.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Akinkugbe provides an overview of exhibitions held between 2022 and 2024 at the Royal Academy in London and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. And she has conversations with curators at other museums, whose work contributes to the understanding of the complexity of black life experiences reflected in contemporary art.

These include Antwaun Sargent (curator of The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion) and Ekow Eshun (curator, In the Black Fantastic and The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure). Akinkugbe also discusses the late Koyo Kouoh’s When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration exhibition. Kouoh, who died in May, was the first African woman to curate the Venice Biennale.

By engaging in dialogue with the curators of these pivotal exhibitions, Akinkugbe demonstrates a shared commitment to uncovering what has been overlooked – and a commitment to deepening the discourse around blackness.

Cautious optimism

Reframing Blackness draws attention to important considerations for museums, curators and higher education institutions. There’s also food for thought for students who are keen to understand some of the factors that have contributed to the historic exclusion of blackness within museum walls and art education.

The book raises key questions that black cultural producers have grappled with in the UK since the 1960s, at the height of the Caribbean artists movement, and during the British black arts movement of the early 1980s. These movements created vital opportunities for discussion around issues of racial justice, visibility and representation.

Following the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in mainstream media in 2020, institutions reacted with pledges for self-reflective work that would lead to more black artists’ work being exhibited and collected. Numerous large exhibitions across national museums followed – some of which are discussed in the book, as are the departmental overhauls of art curricula within higher education.

Portrait d’une Femme Noire by Marie-Guillemine Benoist (1880).

Louvre Museum

I share in some of Akinkugbe’s optimism – but I do so cautiously.

Following the call to decolonise the curriculum, some art departments in UK higher education have expanded their geographic focus beyond the west. Others have stated their intention to address the legacies of enslavement and colonialism through a commitment to diversity and equality in their job advertisements. Some have done both.

But there are a few hurdles that may limit these efforts. First, newer courses that may not attract sufficient interest are often the first to be cut when budgets are constrained.

Second, if courses offer additional modules that attempt to cover vast areas in the global south, there is a risk of overgeneralising entire continents, marginalising them further. Such symbolic gestures fall short in an attempt to challenge art historical frameworks.

Finally, by adding works by black scholars to reading lists as supplementary instead of core reading, their contributions are treated as being on the margins rather than key producers of knowledge.

Museums have a responsibility to reflect the communities they serve, in a way that respects the individual and collective autonomy of that community. This may be counterintuitive to the museum’s original purpose, which may have been to serve the upper class, showcasing its founders’ interests.

Museums are better equipped to engage communities as partners in shaping their future when permanent staff reflect the diversity of these communities across the intersections of race, gender, class, sexuality and disability. Museum directors have a duty to serve these communities with a long-term commitment to care and accountability.

This book asks us to see blackness first. Akinkugbe guides us closer to a vision that does not require black people to reinsert ourselves, but insists on our resolute presence – both then and now.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org, The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Wanja Kimani does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.