A Philosopher Looks at Clothes by Kate Moran is engaging and unpretentious – we need more philosophy books like this

With a few exceptions, philosophers have had little to say about clothes. Maybe this is because the topic seems frivolous, or feminine, unworthy of the attention of a predominantly male collection of thinkers.

Perhaps, too, the transience of fashion, and the fact that clothes belong – quite literally – to the domain of mere appearance, also has something to do with it. In A Philosopher Looks at Clothes, an engaging and informative book, Kate Moran, philosophy professor at Brandeis University in the US, urges us to think again.

As Moran points out, clothing looms large in life. Every day we dress, deciding how many layers to wear and whether we need a coat – or might a cardigan suffice? We gaze critically at other people’s choices (“OMG, those shoes!”). We wonder how to rise to the challenge of an imminent Eurovision-themed party.

From a historical point of view, also, our species-specific recourse to clothes stretches back to the earliest human society. In mythical time, it begins with Adam’s and Eve’s discovery, in shame, that they were naked. If fashion is transient, clothes, per se, are not.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Clothes, Moran tells us, serve three basic purposes: protection, modesty and decoration. At once, these introduce questions of deep philosophical interest. Are the purposes equally important? Why, throughout human history, have we refused to settle merely for protection, desiring for example that a hat should be of some favoured colour or shape? To what extent do our decorative choices express our personal identity? Do clothes ever qualify as works of art? Why is modesty an abiding concern, given that we all know the contours of the unclothed body?

In many contexts, and especially today, clothes invite ethical and political assessment. Clothes communicate a great deal of information about us, including our social position and the causes we espouse.

Read more:

A brief history of the slogan T-shirt

We may knowingly exploit this, choosing to flaunt an obviously expensive garment or to wear our football team’s scarf. In other cases the meanings are imposed. The uniforms forced on prisoners, for example, emphasise subordination and erase their individuality.

Poignantly, research into textile history has uncovered a streak of resistance in even the most ill-treated captives. In concentration camps during the second world war some prisoners altered their uniforms, or mended them, or added pockets. As Moran remarks, these actions were not just practical; their aim, too, was to “recover some sense of identity and dignity”.

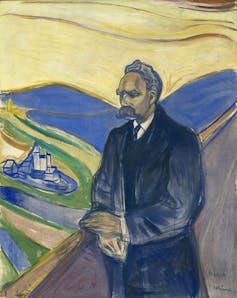

Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche by Edvard Munch (1906).

Thiel Gallery, Stockholm

In the brilliantly conceived series by Cambridge University Press to which this title belongs, each author discusses some general topic from a perspective that is philosophically informed and at the same time personal.

We need more books like these, to counteract the entrenched pretence of disinterestedness in philosophy. (Nietzsche, exceptionally, saw through it, denouncing philosophers as “advocates who do not want to be seen as such … sly spokesmen for prejudices that they christen as ‘truths’”.)

Knowledge of the significance, in an author’s life, of her subject-matter enriches the reader’s imaginative experience of a book. Describing herself as an “ardent hobbyist” who sews her own clothes, Moran provides an additional facet to her account of today’s fashion industry and its scandalous environmental costs.

The reader knows that Moran herself has found an alternative. This lends a certain authority to her judgement that, however futile it may seem for any one person to step off the fast-fashion bus: “There is an important moral difference between being inefficacious and being innocent.”

Moran shows how many areas of philosophy can illuminate the phenomenon of clothes: not only ethics and political thought, but also aesthetics, theories of communication, of personal identity, of gender and cultural appropriation.

For readers unfamiliar with academic philosophy, these forays offer a path into a rich conceptual landscape. Along the way, we are offered a multitude of riveting facts. Who would have guessed that pink has not always been for girls, and blue for boys? And there are pictures, too. My highlight was the “revenge dress” that Princess Diana wore to a gala dinner in the midst of hostilities with Charles, in a successful bid to divert press attention from his appearance on TV.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Sarah Richmond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.