Water wars: a historic agreement between Mexico and US is ramping up border tension

As climate change drives rising temperatures and changes in rainfall, Mexico and the US are in the middle of a conflict over water, putting an additional strain on their relationship.

Partly due to constant droughts, Mexico has struggled to maintain its water deliveries for much of the last 25 years, in keeping with a water-sharing agreement between the two countries that has been in place since 1944 (agreements between the two regulating water sharing have existed since the 19th century).

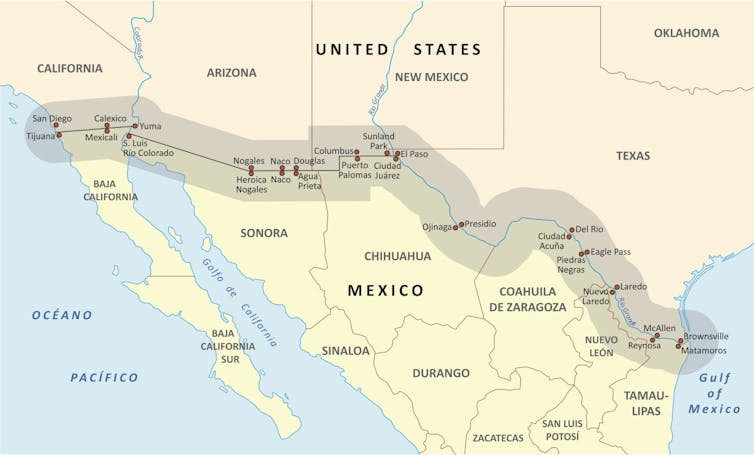

As part of this 1944 treaty, set up when water was not as scarce as it is now, the two nations divide and share the flows from three rivers (the Rio Grande, the Colorado and the Tijuana) that range along their 2,000-mile border. The process is overseen by the International Boundary and Water Commission.

Mexico must send 430 million cubic metres of water per year from the Rio Grande to the US, while the US must send nearly 1.85 billion cubic metres of water from the Colorado River to support the Mexican border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali.

Water deliveries are measured over a five-year cycle, and the current one ends in October. Mexico struggled to deliver its water “debt” in the last cycle which ended in 2020, using waters from reservoirs at the last minute to fulfil its obligations. This left northern Mexico with severely depleted water levels.

Due to growing tensions over water, the Biden administration tried to negotiate and work with the Mexican government to improve the speed with which Mexico’s water deliveries were taking place in 2024.

But with Donald Trump’s return to office, the US has taken a more aggressive stance with Mexico to address its water debts to the US. For the first time in over 50 years, in March of 2025, the US refused to send water from the Colorado River to Tijuana – a city of nearly 2 million people – in order to force Mexico to send more water to Texas.

Mexico has since responded by transferring 75 million cubic metres of water, but this is just a drop in the bucket, as Mexico remains 1.5 billion cubic metres in debt. And this did little to satisfy the Trump administration, which threatened to withhold more water from Mexico. It also demanded the resignation of Maria-Elena Giner, who led the International Boundary and Water Commission, in April.

Rather than looking at diplomatic solutions, Trump has accused Mexico of stealing Texans’ water and has promised to keep escalating consequences if it doesn’t deliver on the treaty terms.

Rainer Lesniewski/Shutterstock

For farmers in Texas, the water shortage has left them unable to plant their crops as they don’t have enough irrigated water to do so. A year ago, the last sugar mill in southern Texas shut down due to the lack of water being delivered by Mexico.

But Mexican farmers believe that the agreement is binding only when Mexico has enough water to satisfy its own needs – and with drought conditions, this means that no excess available water can be sent. Continuing drought conditions in Mexico have plagued farmers in the north, who also rely on water for their crops. Reductions in rainfall in recent years have also left Mexico struggling with water supplies for its own citizens in urban areas.

No running water

In recent years, drought has particularly affected the city of Monterrey in northern Mexico. In 2022, taps ran dry with many of its five million residents without running water for months. Flushing toilets, laundering clothing, washing dishes, bathing all required hauling water by hand from wells.

Locals protested the fact that the best water infrastructure went to factories, not residents. One factor is that water demand has skyrocketed due to more manufacturing in border cities in Mexico.

While increased manufacturing poses one problem, an even bigger problem lies with agriculture, and the types of plants being planted, as well as the way they have traditionally been watered. For example, avocados require 91 litres a day – four times more water than the production of oranges, and ten times more than the production of tomatoes.

Alfalfa is another thirsty crop being mass produced in drought-prone states, such as Texas, California and even Arizona.

Citizens in Mexico City sometimes faced weeks of water shortages in recent years.

As much as 80% of the Colorado River basin’s water is used for agriculture and about half of that goes towards the production of alfalfa. Even more concerning is that most of the water is going to feed these thirsty crops. And in the dry south-west states of the US half of its water goes to towards the production of beef and dairy cattle.

This has an impact on cities who are completely dependent on the Colorado River. In the case of Tijuana in Mexico, the Colorado River supplies 90% of its water, while US cities such as Los Angeles and Las Vegas receive 50% and 90% of their water supplies from the Colorado River and basin, respectively.

This is a major concern as both the Colorado River and the Rio Grande are experiencing record low levels of water. And getting more water from Mexico is not a long-term solution.

Though the Biden administration was criticised by farmers for not threatening Mexico, by withholding water, its approach largely focused more on the long-term challenges.

For the previous US administration the solution was to invest more in the Colorado River basin, incentivising California, Arizona and Colorado to conserve three million acre-feet of water through 2026 in return for US$1 billion (£741,000,000) in federal funding.

What drives this conflict?

But under Trump, federal funding for tackling climate change is being slashed. Increased polarisation in US domestic politics and growing tensions between the US and Mexico will make resolving this crisis all the more difficult.

This is a missed opportunity. Even though conflicts over water are becoming more frequent, water scarcity can also be a potential driver of cooperation.

Meanwhile, the US’s relationship with Mexico continues to be rocky. Trump has threatened to put new 30% tariffs on Mexico from August 1, after he claimed it hadn’t done enough to tackle drug cartels.

Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has said her government was destroying drug laboratories every day, and that the US must control weapons travelling over its border into Mexico which were being used for criminal purposes. Meanwhile, high tariffs on Mexican goods are likely to affect US consumers as Mexico is currently the US’s biggest trading partner.

Cooperation, and acknowledging the role played by climate change, and unsustainable forms of development in both agriculture and manufacturing are key to resolving this cross-border water crisis – but these are things that the Trump administration is unlikely to acknowledge, or address.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Natasha Lindstaedt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.