Windrush scandal: those left to apply for compensation without legal help missed out on tens of thousands of pounds

The Windrush scandal has been one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in Britain, affecting tens of thousands of people. The government set up a scheme in 2019 to award compensation to those who had been wronged by racist immigration legislation over decades, left unable to prove their immigration status.

But in a new report, I have found that how much victims receive through the scheme has little to do with how they were wronged, and more to do with whether they can access a lawyer. Those who applied without legal support were offered tens of thousands of pounds less than when they appealed with legal representation.

The research, produced with law reform charity Justice and Dechert LLP’s pro bono team, provides empirical evidence of precisely what lawyers do that makes a difference.

Our research participants, who were claiming compensation over the Windrush scandal were offered, on average, £11,000 when applying to the scheme without a lawyer. But when applying for review with legal representation, the award was more than £83,000. One of our participants was refused any compensation when he applied alone, but eventually received £295,000 with the help of a lawyer.

Why lawyers are needed

We conducted an in-depth review of ten files where a claimant first applied for compensation without a lawyer, received a refusal or a low offer of compensation, and then applied with a lawyer for review of that decision.

We reviewed another seven files from people who could never have claimed alone, because of street homelessness, dementia or serious health conditions.

The team interviewed each lawyer and (where possible) the claimant, to identify exactly what a lawyer does that makes a difference.

The Home Office insists lawyers are unnecessary because the scheme’s own caseworkers will help find evidence. But our findings suggest serious failings in those efforts. One of the main contributions of lawyers was expertise in finding decades-old evidence and demonstrating how it meets the standard of proof for the Windrush compensation scheme.

One of our claimants applied for compensation for having been refused housing assistance (leaving her homeless) based on a misunderstanding of her immigration status. The Home Office caseworkers emailed her local council and asked whether there was a record of her being refused housing assistance 20 years earlier. The council replied that there was not. The caseworker treated that as evidence that she had never made an application.

When a lawyer got involved, he asked the council to confirm how long they kept housing application records. The answer was 12 years, so there was never any prospect of evidence existing from 20 years ago. The lawyer then managed to track down her housing file with the housing solicitors who represented her.

Lawyers knew how to request files from public bodies, understood the references to statutes in those files and, most importantly, were able to spot when key documents were missing.

The lawyers in the cases we reviewed took detailed witness statements from claimants. Those made by claimants alone averaged 1.5 pages, whereas those made by lawyers were at least 15 pages, containing far more relevant detail showing how the claimant met the scheme criteria.

Lawyers acted as a “buffer” between claimant and Home Office. Claimants told our research team that they felt the Home Office spoke to them with more respect once they had a lawyer. Often, claimants were ready to give up and accept the refusal because they were exhausted and frustrated with fighting the Home Office.

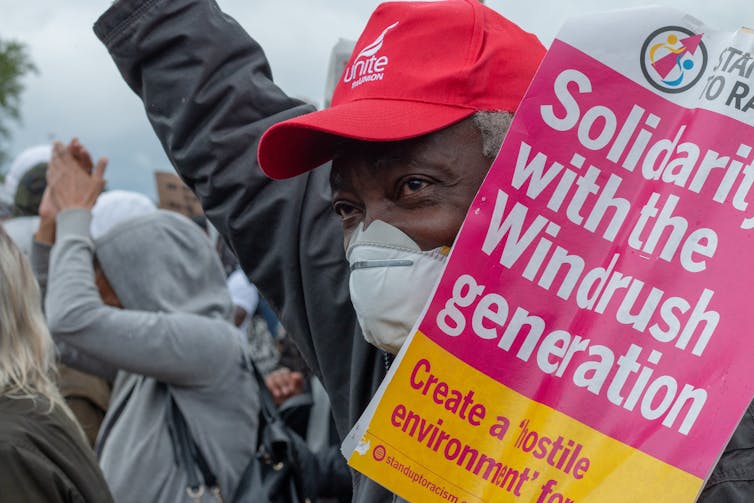

The Windrush scandal has affected tens of thousands of people.

James Ivor Wadlow/Shutterstock

The findings are consistent with other peer-reviewed research exploring what lawyers or representatives add to cases in the family courts and the tribunals: a 15%-18% “representation premium” in chances of success. In some cases, this can be achieved through pre-hearing advice.

All of our participants had a lawyer either through Law Centres funded by a charity, a university law clinic, or private law firms doing the work pro bono. Some firms also do the work on a no-win-no-fee basis, typically taking 25%-30% of the claimant’s damages but on occasion up to 67%. Given that it takes 32-103 hours to prepare the case, the lawyer’s fee may still underrepresent the work they did.

Compensation schemes and legal support

Recent reports have revealed serious problems with the compensation schemes for both the Post Office and the infected blood scandals. The chairs of the respective public inquiries, Sir Wyn Williams and Sir Brian Langstaff, criticised gaps in the provision of access to legal advice and recommended funded legal advice for all claimants.

The Post Office Horizon IT scandal has four compensation schemes for different categories of victim. In each, claimants can choose between a fixed payment (£75,000) or an individual assessment of loss. In three of those schemes, funded legal advice is available to help claimants choose between those options. In the Horizon Shortfall Scheme, though, it is not available unless and until they reject the fixed payment and opt for individual assessment.

The infected blood compensation scheme includes funded legal representation for “core” route claimants – those directly affected. But the inquiry report says it should also be available for claims by affected family members.

Only the Windrush scheme has no provision at all for funded legal representation at any stage. All representation is either a matter of charity, or paid for from the damages, which may leave very little for the claimant.

Yet the Windrush scheme is arguably the most complicated, with a 44-page claim form compared with just eight for the Horizon Shortfall Scheme. The infected blood claim form is largely completed by medical personnel. The Windrush scheme has complex eligibility requirements compared with the other schemes, and often demands an immigration lawyer’s expertise.

As our research found, lawyers were able to advise Windrush claimants on whether the offer of compensation was fair or whether they should apply for review. Our empirical evidence, along with the reports, suggest all compensation schemes involving state harm to citizens should include free legal representation for claimants.

In response to the report, a Home Office spokesperson told the Guardian: “Earlier this year, we launched a £1.5m advocacy support fund to provide dedicated help from trusted community organisations when victims are applying for compensation. However, we recognise there is more to be done, which is why ministers are continuing to engage with community groups on improvements to the compensation scheme, and will ask the new Windrush commissioner to recommend any further changes they believe are required.”

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Jo Wilding does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.