Who is Odysseus, hero of Christopher Nolan’s new epic?

Somewhere between hero and hustler, family man and philanderer, king and con artist, Odysseus is one of ancient literature’s most complex figures. In the Iliad, he is the mastermind behind the Trojan horse.

In Homer’s Odyssey, he is the protagonist of a ten-year journey home – one that sees him encounter gods, monsters, temptations and profound moral dilemmas. Next year, he will be the hero of a new Christopher Nolan epic, and played by Matt Damon.

Odysseus’s journey from Troy to Ithaca in the Odyssey is anything but a straight line. It’s an epic zigzag through storms, temptations, divine grudges and existential threats. Instead of returning in weeks, he spends a decade adrift.

He is stranded by nymphs, resists sirens and watches his crew perish one by one. Every stop tests not only his wit but his very sense of self.

The Odyssey isn’t a tale of noble perseverance. It’s a study in survival. Odysseus deceives, disguises and entangles himself in morally grey romantic liaisons with a sorceress (Circe), nymph (Calypso) and princess (Nausicaa). He does so often as strategist and sometimes as willing participant.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

In Homer’s world, infidelity is a tool of survival. Odysseus survives not through moral clarity, but through his moral agility. His loyalty to his wife Penelope (reportedly played by Anne Hathaway in the new adaptation) is longitudinal, not linear. His compass is always aimed at returning to Ithaca, if not always in a straight line.

Would this flexibility pass modern ethical scrutiny? Probably not. But what made him successful wasn’t moral integrity – it was his ability to navigate each situation, even if that meant bending the rules.

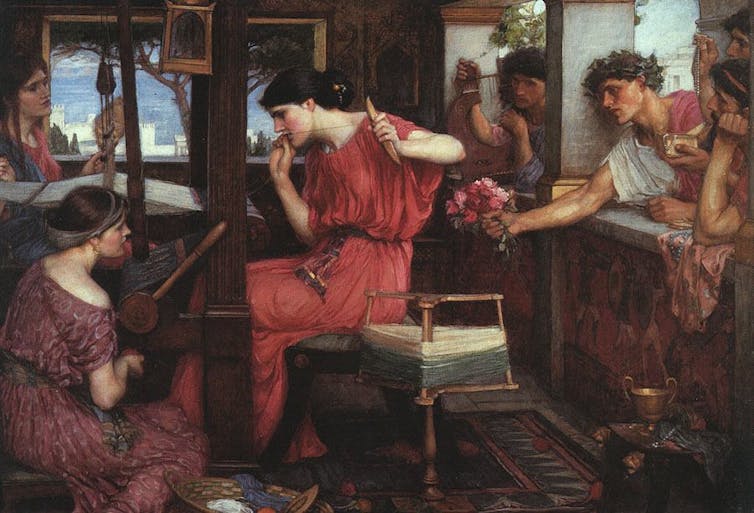

While Odysseus adapts, Penelope endures with strategic resilience. For 20 years, she fends off suitors with deft delay tactics. She avoids them by weaving and unweaving a funeral shroud for her husband’s father, Laertes. It’s a defiant, slow motion resistance campaign, waged with thread and silence.

Penelope and the Suitors by John William Waterhouse (1912).

Aberdeen Art Gallery

If Odysseus navigates external monsters, Penelope masters the domestic battlefield. Her fidelity in her husband’s absence is deliberate, political and astute. In a patriarchal world, her power lies in pause. Her story is one of emotional labour and strategic survival.

Narrative loops and non-linear journeys

The Odyssey is an ancient masterpiece of non-linear storytelling. It begins in the middle of the action and uses nested narratives, flashbacks and shifting voices. Odysseus tells much of his own story, reframing events from his point of view and reshaping himself in hindsight. Memory becomes montage. Truth bends to necessity. Fact and fiction bleed into one another.

Homer doesn’t just tell a story – he constructs a labyrinth. The Odyssey anticipates the fractured forms of modernist literature and cinema, where identity is unstable and time itself is malleable.

Odysseus and Penelope by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1802).

Wiki Commons

When Odysseus finally returns to Ithaca, disguised as a beggar and quietly assessing his ship’s wreckage, it’s no romantic climax. It’s a calculated risk. Penelope doesn’t swoon; she tests. Only when he passes her intimate knowledge test – he reacts with outrage when she suggests moving their bed, which he built around a living olive tree – does she relent. Their reunion is not a Hollywood embrace but a wary negotiation.

It signals restoration, yes. But also mistrust, trauma and mutual testing. Homecoming, like survival, is complicated.

Odysseus is not a flawless hero. He is a survivor who negotiates with monsters, debates with gods and crawls home disguised as a beggar. A man shaped as much by cunning as by consequence.

Would Odysseus pass a modern ethics exam? Certainly not. Would he charm the professor, flip the question and still walk out with an A? Absolutely. Some stories endure not because they are true, but because they were told by survivors.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.