When US and Japanese troops stopped fighting to talk, eat and pray together

Japan’s Emperor Hirohito ordered his country’s surrender in a radio broadcast on August 15 1945. After the deaths of some 70 million people, the second world war had finally come to an end.

Reflections on the anniversary of the conflict’s end often turn, understandably, to the cataclysmic atomic bombings of Hiroshimi and Nagasaki that precipitated the emperor’s decision.

But to research a strikingly different – and little-known – story from the final stages of the war in the Pacific, we recently travelled to the remote Japanese island of Aka, where a scarcely believable truce between US and Japanese soldiers took place 80 years ago. In the shadow of one of the war’s fiercest battles, enemy combatants stopped fighting to negotiate, exchange souvenirs, eat – and even pray together.

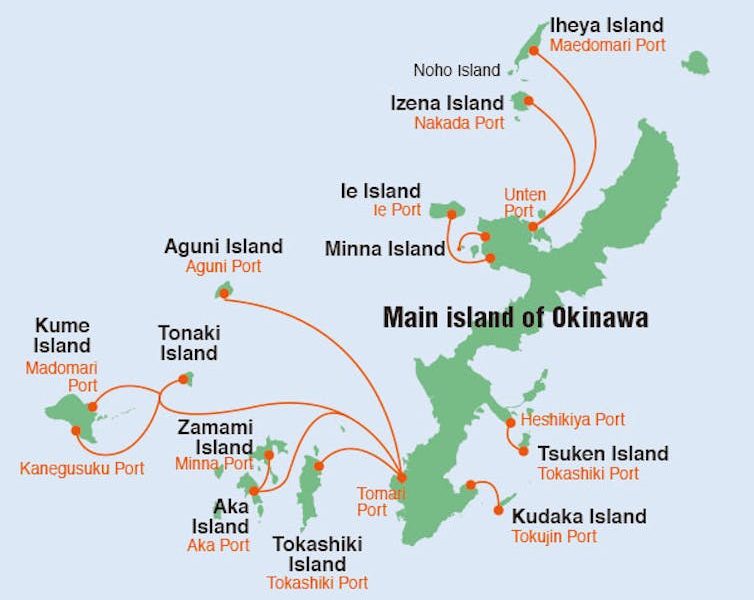

Aka is part of the Kerama Islands group in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan.

Okinawa Island Guide

The battle of Okinawa was the last great engagement of the second world war, and one of its most terrible. The US and UK saw Okinawa as a staging post to the full-scale invasion of mainland Japan, some 400 miles further north. For Japan, defending Okinawa was a way to prolong the war and strengthen its hand in eventual peace negotiations.

To prepare for a battle of attrition, the Japanese army spent months fortifying Okinawa. Sheltering in tunnels and caves, the troops were largely unscathed by a massive initial US air and naval bombardment. They emerged to fight what historian Yunshin Hon called a “three-month orgy of killing”.

After ten weeks of intense combat, the battle was lost. Rather than surrender, before committing ritual suicide, the Japanese commanding generals Mitsuru Ushijima and Isamu Chō issued a final communique ordering every man to “fight to the end of the sake of the motherland … Do not suffer the shame of being taken prisoner.”

Okinawa’s Cornerstone of Peace memorial records the names of more than 240,000 people who died in the battle – more than half of them Okinawan civilians. The Japanese army coerced the civilian population into mass collective suicides, with family members killing each other to prevent them falling into the hands of US troops.

Given this horror, the events on Aka island, 15 miles west of Okinawa, are all the more extraordinary. Using declassified military reports, interviews with participants and eyewitnesses plus archives held by their relatives, we were able to piece together this forgotten story.

An unlikely truce

The Aka operation began on June 13 1945, led by led by US marine reservist Lt. Col. George Clark. About a dozen American soldiers and marines had volunteered for the dangerous mission of going ashore to secure the surrender of a 200-strong Japanese garrison, concealed in the jungle.

The US operation was supported by Japanese prisoners who, having been persuaded of the futility of further deaths in a now-unwinnable war, broadcast appeals for the garrison to surrender from portable loudspeakers.

There was no initial response from the Japanese. But on June 19, the final day of the scheduled mission, the team spotted some civilians. In his official report, Clark recounted that “in a last desperate attempt to save the day”, Lt. David Osborn (a US marine officer who had volunteered to help Clark lead the expedition) “plunged into the water and, naked with the exception of a pair of white skivvy shorts, made off in hot pursuit”.

In the dense undergrowth, the unarmed Osborn stumbled across a Japanese soldier who, remarkably, did not harm him. Instead, the garrison commander, Major Yoshihiko Noda, agreed to meet the Americans – but only if they were accompanied by an old comrade of his, Major Yutaka Umezawa, who had been injured and taken prisoner at the start of the battle.

On June 26, the team returned to Aka (with Umezawa carried on a stretcher), landing on the remote Utaha beach for this conference between Noda and Clark. Umezawa – whose views on the Americans and the war had been transformed by his benign treatment in captivity – strove to persuade Noda of the futility of suicidal resistance.

As negotiations continued, Clark had lunch brought onto the beach and shared with the Japanese: pork and sweet potatoes for the officers, canned goods for the men.

In his official report, Clark noted this led to “the most amazing spectacle it has ever been my lot to behold … On the sand dunes and on the beaches were Jap soldiers and officers, United States marines, soldiers, sailors who had brought in the food, Jap prisoners, officers as well as enlisted men, white folks, black folks, yellow folks; a general melee if there was ever one.”

As a gesture of mutual trust, Noda invited Osborn and another officer, Lt. Newton Steward, back to his command post. He had his men wash and dry the Americans’ shirts, which had become sweaty during the negotiations, and served them tinned pineapple. The Americans then left the island with Noda promising a formal response the next day.

When the marines returned on June 27, Noda’s adjutant, Second Lt. Yoshiyuki Takeda, informed Clark that, regrettably, they were unable to surrender without permission from the emperor. However, the two sides agreed a tacit truce. Noda promised that if the Americans refrained from military action, their men could go “hunting shells or swimming along the beaches” without danger.

In a remarkable final gesture, Clark asked Takeda “if he would like to join the group in a prayer to the Supreme Being of all faiths for international understanding and peace”.

In his report, Clark wrote that Takeda “readily agreed” and, as US and Japanese soldiers knelt together by the shore in prayer, was “visibly moved, arose and thanked us all when the gist of the prayer had been interpreted for him”.

Clark left the island disappointed that he had failed to secure a surrender. However, the truce held until the end of the war. It prevented further Japanese and US military casualties, and spared the island’s inhabitants the devastation that was unleashed on the rest of Okinawa.

Shared humanity

The Aka truce was an isolated event, and we should not romanticise it. Noda’s garrison was responsible for the deaths of a dozen starving Korean conscripted labourers at the start of the battle for Aka, executed for “theft” when they were found with rice stuffed in their pockets.

But like the 1914 Christmas truces on the western front, the Aka truce captures the imagination – and we believe offers three instructive and hopeful lessons.

First, even in the most appalling of circumstances, enemy combatants were able to recognise each other’s shared humanity. They attended to basic needs of food and comfort, and joined together in a moment of spiritual intimacy that transcended cultures.

Second, it showed that enemy soldiers were able to enter into dialogue and choose not to continue fighting – risking not only immediate death or injury, but also future courts-martial. This raises the ethical question: “Do soldiers on the battlefield have the right not to fight?” It is a right that soldiers have increasingly sought to assert, in contexts ranging from Vietnam to the occupied Palestinian territories.

Finally, the Aka truce offered a glimpse of the subsequent Allied-Japanese reconciliation that seemed unthinkable at the time. On the 80th anniversary of the end of history’s most terrible war, that is a story and message worth retelling.

Nick Megoran received funding for this research from Hakusem Partners Ltd, Sapporo City, Japan. He is grateful to the Director, Yasuhiro Kawamoto.

Hiroshi Sakai received funding for this research from Hakusem Partners Ltd, Sapporo City, Japan. He is grateful to the Director, Yasuhiro Kawamoto.