William Blake’s painting The Ghost of a Flea speaks to processing childhood trauma

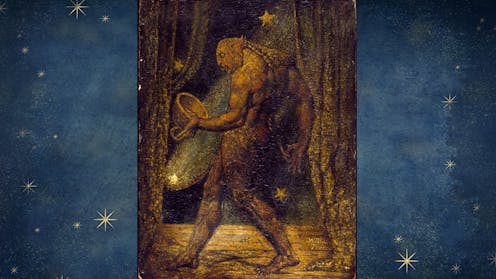

The Ghost of a Flea by William Blake (1819-1820). Tate Britain/Collage made with Canva

In William Blake’s painting The Ghost of a Flea (1820) a huge muscled figure fills the frame. He steps forward, the right side of his body towards the viewer. In one outstretched hand he holds a bleeding bowl (used to catch the blood released during bloodletting) made from an acorn. In the other, a curved thorn stands in for a knife. His tongue protrudes from between his teeth and his eyes bulge from his head. His ears are pointed with frills, or gills, almost reptilian.

White paint dots his eye, so that he appears to be both looking ahead and looking at us. He is stood on a stage between curtains with a backdrop of stars, one falling in a blaze of light. He is at once light and heavy, balanced on his toes as if he is engaged in a dance, or creeping towards his victim.

Painted in thick brown tempera (a pigment bound in water and egg, or oil and egg) and cracked with age, it is gold leaf that gives the painting its light. It’s in the creature’s muscles, the stars that fall behind him, the rim of the acorn bowl, the curtains he parts with his bulk and the boards of the stage that break into undulations at his step. The whole effect is one of movement, and of a creature occupying a space that is both vast and framed. But the painting is tiny – a rectangular hardwood panel measuring only 8.42 by 6.23 inches.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

The Ghost of the Flea is a development of an original sketch from a group of visionary heads (chalk and pencil drawings of historical and mythical characters seen in visions) that Blake had drawn for watercolour artist and astrologer John Varley. Blake claimed to have seen and spoken with spirits since he was a child and in a series of late night seances, Varley persuaded Blake to draw the images of these visions to illustrate his book, Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy (1828).

My poem of the same title, in my 2018 collection, A Perfect Mirror, recalls Blake’s vision of the flea’s ghost as a way of writing about a series of terrifying experiences I had as a child. Blake’s monstrous “ghost” is the perfect embodiment of a horror I could neither name nor give shape to for many years: “The corner of the bedroom housed him / gigantic in a speck of dust.”

These experiences, triggered by trauma, involved a level of disassociation where I would lose all sense of scale, my body in space becoming both impossibly tiny and horrifically vast: “at once huge / and far away, immensely tiny and close.”

Blake’s painting captures the paradox of this disembodiment. The flea’s ghost is not what we expect of the tiniest of creatures, but instead expresses the flea’s innermost essence.

I grew up during the cold war, when the threat of nuclear annihilation was close at hand. This threat affected me deeply. My sense of horror was not only a personal one, but one that stretched to imagining the millions of souls that would be released from their bodies by nuclear catastrophe. In my poem, the white eyes of the flea’s apparition become “soft white pods of spider nests / where the million bodies might / any minute come rushing”.

While acknowledging the horror and giving it form, the poem self-consciously steps back from it. Now I am the poet, looking back on the experience and framing it through art. The process of writing, or any other artistic process, is only therapeutic in how far writing (or painting) is able to distance the traumatic experience from the writer.

The artist or writer does this through the process of shaping, crafting, rewriting and editing. The very act of “framing” draws attention to the artistic process. As Blake “frames” his monster in paint between draped curtains on the tiny hardwood panel I, the poet, frame and shape the frightening memories and images in lines and stanzas. This is the “stage” whereby experience is transmuted through the artifice of the painting or poem.

William Blake in Conversation with John Varley by John Linnell (1818).

Wiki Commons

Images are central to this process in poetry and in visual art, but it is often in visual art that these images are more readily available. Powerful visual images can work like dreams, coding meaning and experience in ways that reach the subconscious mind and impart understanding that might otherwise stay hidden. Without needing to fully articulate an experience, it must be “proved upon our pulse”, as the poet John Keats put it.

This is only one of the reasons I am drawn to ekphrastic writing (writing that describes another art form). To my mind, the purpose of ekphrasis goes far beyond this. The poem must do more than simply recreate or describe the work of art – it should be a conversation between art forms that can range from discussing to expanding, or stepping off from the ideas and motifs the original works evoke. Most importantly, ekphrastic work should not only be a synthesis of the original and of new ideas and thinking, but a new work of art that stands in its own right.

My intention in my poem The Ghost of a Flea was to hold such a conversation with Blake through his painting, The Ghost of a Flea. Blake is a poet and artist who speaks profoundly to my own personal and artistic experience – and whose work remains a well of inspiration and encouragement.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Sarah Corbett’s suggestion:

Laurie Anderson in 2020.

New Zealand Government, CC BY-SA

An image of the doomsday clock opens Laurie Anderson’s artwork, the “opera” Ark, which blends song and story with images in a three-hour essay about the apocalypse.

As a child, I would “see” the doomsday clock on my bedroom wall, counting me down to my own destruction. I had to count back from 100 to hold in balance the second hand of the clock that threatened to strike the hour of midnight. At the last moment I would find the courage to escape from my room, and the nightmare would vanish, only to return the next evening.

Despite the multiple threats humanity now faces, from nuclear war to AI to climate collapse, Anderson’s performance looks for ways to bring us together in a collective healing. I found poetry – or perhaps, more accurately, poetry found me. The function of art is not only to awaken us to the truths around us, but to give us ways to re-imagine our future.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Sarah Corbett received funidng from the AHRC for Doctoral study, 2007 – 10