‘Gas station heroin’: the drug sold as a dietary supplement that’s linked to overdoses and deaths

US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Regulatory Affairs, Health Fraud Branch

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an urgent warning about tianeptine – a substance marketed as a dietary supplement but known on the street as “gas station heroin”.

Linked to overdoses and deaths, it is being sold in petrol stations, smoke shops and online retailers, despite never being approved for medical use in the US.

But what exactly is tianeptine, and why is it causing alarm?

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Tianeptine was developed in France in the 1960s and approved for medical use in the late 1980s as a treatment for depression.

Structurally, it resembles tricyclic antidepressants – an older class of antidepressant – but pharmacologically it behaves very differently. Unlike conventional antidepressants, which typically increase serotonin levels, tianeptine appears to act on the brain’s glutamate system, which is involved in learning and memory.

It is used as a prescription drug in some European, Asian and Latin American countries under brand names like Stablon or Coaxil. But researchers later discovered something unusual, tianeptine also activates the brain’s mu-opioid receptors, the same receptors targeted by morphine and heroin – hence it’s nickname “gas station heroin”.

As a prescription drug, tianeptine is sold under various brand names, including Stablon.

Wikimedia Commons

At prescribed doses, the effect is subtle, but in large amounts, tianeptine can trigger euphoria, sedation and eventually dependence. People chasing a high might take doses far beyond anything recommended in medical settings.

Despite never being approved by the FDA, the drug is sold in the US as a “wellness” product or nootropic – a substance supposedly used to enhance mood or mental clarity. It’s packaged as capsules, powders or liquids, often misleadingly labelled as dietary supplements.

This loophole has enabled companies to circumvent regulation. Products like Neptune’s Fix have been promoted as safe and legal alternatives to traditional medications, despite lacking any clinical oversight and often containing unlisted or dangerous ingredients.

Some samples have even been found to contain synthetic cannabinoids and other drugs. According to US poison control data, calls related to tianeptine exposure rose by over 500% between 2018 and 2023. In 2024 alone, the drug was involved in more than 300 poisoning cases. The FDA’s latest advisory included product recalls and import warnings.

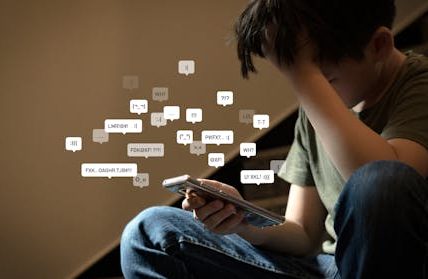

Users have taken to the social media site Reddit, including a dedicated channel, and other forums to describe their experiences, both the highs and the grim withdrawals. Some report taking hundreds of pills a day. Others struggle to quit, describing cravings and relapses that mirror those seen with classic opioid addiction.

Since tianeptine doesn’t show up in standard toxicology screenings, health professionals may not recognise it. According to doctors in North America, it could be present in hospital patients without being detected, particularly in cases involving seizures or unusual heart symptoms.

People report experiencing withdrawal symptoms that resemble those of opioids, like fentanyl, including anxiety, tremors, insomnia, diarrhoea and muscle pain. Some have been hospitalised due to seizures, loss of consciousness and respiratory depression.

UK legality

In the UK, tianeptine is not licensed for medical use by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and it is not classified as a controlled substance under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. That puts it in a legal grey area, not formally approved, but not illegal to possess either.

It can be bought online from overseas vendors, and a quick search reveals dozens of sellers offering “research-grade” powder and capsules.

There is little evidence that tianeptine is circulating widely in the UK; to date, just one confirmed sample has been publicly recorded in a national drug testing database. It’s not mentioned in recent Home Office or Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs briefings, and it does not appear in official crime or hospital statistics.

But that may simply reflect the fact that no one is looking for it. Without testing protocols in place, it could be present, just unrecorded.

Because of its chemical structure and unusual effects, if tianeptine did show up in a UK emergency department, it could easily be mistaken for a tricyclic antidepressant overdose, or even dismissed as recreational drug use. This makes it harder to diagnose and treat appropriately.

It’s possible, particularly among people seeking alternatives to harder-to-access opioids, or those looking for a legal high. With its low visibility, online availability and potential for addiction, tianeptine ticks many of the same boxes that once made drugs like mephedrone or spice popular before they were banned.

The UK has seen waves of novel psychoactive substances emerge through similar routes, first appearing online or in head shops, then spreading quietly until authorities responded. If tianeptine follows the same path, by the time it appears on the radar, harm may already be underway.

Michelle Sahai does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.