Jane Austen was a satirist – why isn’t she treated like one?

From the pompous vanity of Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion (1817), to the shallow reading habits of Isabella in Northanger Abbey (1817), few characters in the works of Jane Austen are spared the gentle satire of her famously ironic narrative voice. Similarly, some of her best remembered characters, like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice (1813), are more than willing to share a sarcastic retort or wry observation.

And yet, Austen, like many other women writers of the period such as Frances Burney, Eliza Haywood and Mary Robinson, are almost always missing from histories of satire. This is less to do with whether their works were satirical – because they blatantly were – and more to do with our problematic understanding of satire.

Satire, as writer Dustin Griffin states, is typically defined as a work designed to “attack vice or folly”, using “wit or riducule” and engaging “in exaggeration and some sort or fiction.”

This article is part of a series commemorating the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. Despite having published only six books, she is one of the best-known authors in history. These articles explore the legacy and life of this incredible writer.

Austen, like so many women, used satire and humour to critique her situation in a patriarchal society and, in so doing, persistently challenged deeply ingrained assumptions about women’s status as the passive, subordinate property of men. As literary critic Rachel Brownstein memorably put it, women at the time experienced a constant doubleness that frequently became “the ironic self-awareness of a rational creature absurdly caught in a lady’s place”.

And yet, when asked to name 18th-century satirists, it is so often the case that we are confronted with the same list of authors: Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Alexander Pope, author of The Dunciad (1728), and sometimes Henry Fielding, author of Tom Jones (1749). Typically the thread isn’t then picked up again until a century later, when we are offered Charles Dickens (in works such as The Pickwick Papers (1837), William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848) and Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now (1875).

However, there are so many examples of brilliant satire written by women at the time.

Take for instance, The Art of Ingeniously Tormenting (1753) by Jane Collier. A satirical conduct book which, rather than advising young women on how to become delicate, feminine creatures, instead gave them tips on how to torment their husbands. Why kill your spouse, it cheerfully asks, when it will be far more satisfying to “waste them by degrees”, effectively killing them slowly across a lifetime of nagging.

There was also Eliza Haywood’s satirical periodical The Parrot (1746), which adopted the perspective of a green parrot in a cage, tired of being objectified and written off as a “pretty prattler”.

Sarah Scott’s Millenium Hall (1782) is about a group of women deciding to abandon patriarchal society altogether and establish a women-only commune. It is full of withering observations. While Mary Robinson’s Walsingham (1797) exposes the many contradictions of 18th-century Britain’s sexist society by telling the story of a girl raised as a boy by parents anxious to have a male heir.

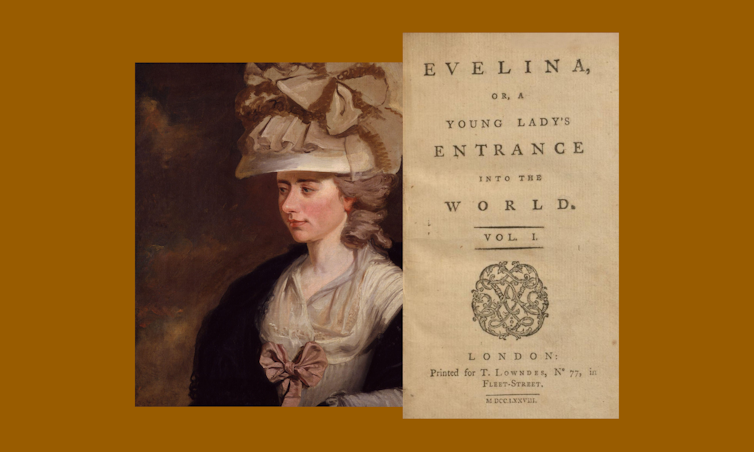

Frances Burney’s Evelina skewered Bath’s fashionable society.

Wikimedia

As a girl, Austen loved Frances Burney’s Evelina (1778), a novel about a young woman who, upon arriving in Bath for the first time, cannot stop laughing at the utter absurdity of fashionable society. (Evelina is also a novel in which a monkey wearing a suit appears out of nowhere, goes berserk, and is never mentioned again. You should read it immediately.)

Similarly, the anonymous novel The Woman of Colour (1808), sees a young heroine born in Jamaica, Olivia Fairfield, travelling to England to secure her inheritance only to discover the high society she’d been raised to admire is in fact barbarous and stupid. As both spectacle and spectator, Olivia becomes a powerful engine for satire.

Even Charlotte Brontë deployed satire. Brontë was an admirer of William Makepeace Thackeray and dedicated the second edition of Jane Eyre (1847) to his famously satirical novel Vanity Fair (1848). As 19th-century literature expert Jo Smith has recently observed, Brontë also used her persona, Currer Bell, to enact satire across her career, even articulating her own theory of satire.

The subtle barb instead of the violent attack

That these women’s names don’t come up in lists of great satirists of the period is partly due to the availability of their writing. Many of the texts I’ve mentioned have only been recovered and made publicly available again over the last 50 years. But it is also to do with how we talk about satire.

The purest definition of satire is that it performs a critique of something that the author finds to be ridiculous, stupid or dangerous, and uses some kind of distortion as part of this critique. This usually takes the form of exaggeration, but can also be inversion or allegory.

However, you’ll notice that when people talk about satire they often describe the lash of the satirist’s whip, or the slash of the surgeon’s scalpel. Satire is talked about as biting, skewering and violent.

Jane Austen found much to skewer in Regency society and does so deftly in her books Persuasion and Northanger Abbey.

Wikimedia

The satirist, from the Roman poet Juvenal through to John Dryden and Jonathan Swift, is often imagined as a heroic aggressor, whose righteous indignation drives him to lash out at a fallen world. This is an image born of Renaissance theories of satire, and one slightly modified (but heavily promoted) during the endless, rarely objective, debates about what satire should be that dominated the 18th century.

As a result, we end up with a definition of satire that is coded in masculine language. So many definitions, even today, talk about satire “attacking”, rather than “critiquing”. But in Austen, and the work of her female contemporaries, we see another kind of satire. The joy of so many of the quips and rejoinders issued by characters like Anne Elliot and Elizabeth Bennet is that often their targets don’t even realise they have been satirised, so subtle is the critique.

Virginia Woolf said it best when called upon to describe Austen’s juvenilia, in particular her early novel Love and Freindship sic:

What is this note, which never merges in the rest, which sounds distinctly and penetratingly all through the volume? It is the sound of laughter. The girl of 15 is laughing, in her corner, at the world.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and contains links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Adam J Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.