How existential philosophy can help you to cope with anguish

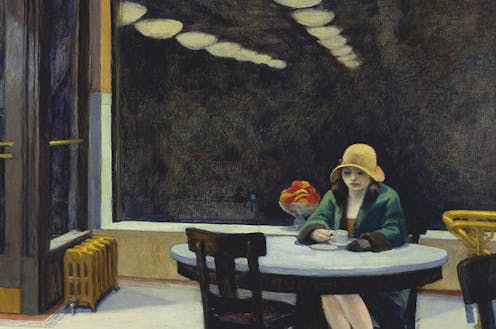

Automat by Edward Hopper (1927). Des Moines Art Center

“Am I with the right person?” Most of us have probably asked ourselves this question at least once in our life. I certainly have.

To help you out, your friends might ask: “Well, do you love them?” Then you go home and the conversation goes around in your head. “Yes, I love them!” you tell yourself. But how can you be sure? Are you ready to spend your whole life with just one partner?

The stomach flip you may have just had when reading the words “your whole life” is the emotion known as anguish – the overwhelming fear you feel when confronted with a big choice. I have felt anguish myself in this situation – and the philosophy of existentialism really helped me to make sense of it.

But let’s start from the beginning: why do we feel anguish? It arises from uncertainty – in our example, from the choice between staying with the person you’re with for a lifetime, or breaking up.

Anguish is the result of a conflict between two values that we equally cherish: in this case, love and freedom. It is painful because we want both options but can only have one, as they pull us in opposite directions.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) argued that anguish arises because we are free. And, contrary to what most of us think, we don’t like freedom. Or at least, we like a decent degree of it, but certainly not as much of it as we actually have.

What we like more than freedom is certainty. Suppose I happen to possess a formula that will tell you with absolute certainty what is the best course of action for every decision you have to make in your life. You would feel no more anguish, and would have no doubt that the decision you made is the best one.

Would you want this formula? If the answer is yes, you have just admitted that certainty matters more to you than freedom.

People who conceive of themselves as being independent might think they want freedom more, and refuse my formula. They may even claim that they don’t mind feeling anguish. But chances are they’re yet to be faced with the biggest decisions a human being can encounter.

These people haven’t experienced freedom to the extent that it induces real anguish. After all, anguish is a clear sign of discomfort (which can even be felt physically) – and if we didn’t want certainty, we wouldn’t feel it in the first place.

Can anguish be overcome?

The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) said that anguish can’t be overcome. But there’s reason to disagree.

First, you need to understand that anguish is an intrinsic feature of life. Accept this, and you will be a little less scared by it.

What you also have to accept is that no one has the formula I described earlier. This may seem trivial, but when a big decision looms over us, sure enough we long for certainty and this formula. There is usually no objective “ideal” course of action, though.

The Monk by the Sea by Caspar David Friedrich (1808-10).

Old National Gallery, Berlin

Of course, we may have the illusion that we made the “right” or “wrong” choice in a certain situation. But that is narrative fallacy – meaning that in reality, we simply don’t know what would have happened had we made another decision.

Then comes the hard part. It takes courage to choose what you think is right for you. You should take comfort, though, in the fact that no one usually knows what’s most right for you better than yourself.

Insightful suggestions from good friends or families just uncover information that was already within you. No one sincerely accepts other people’s values if they weren’t theirs in some way already.

Study yourself, establish what beliefs you cherish over others, and start from there. If your choices are the consequences of your deepest beliefs, they are less likely to feel wrong or uncertain. Release the demand for certainty, and you’ll have neutralised anguish.

Luca Costa receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).