Why Islamic State is expanding its operations in north-eastern Nigeria

Islamic State West Africa Province (Iswap), one of the most powerful global affiliates of the Islamic State jihadist organisation, is in the middle of its largest offensive against the Nigerian military in years.

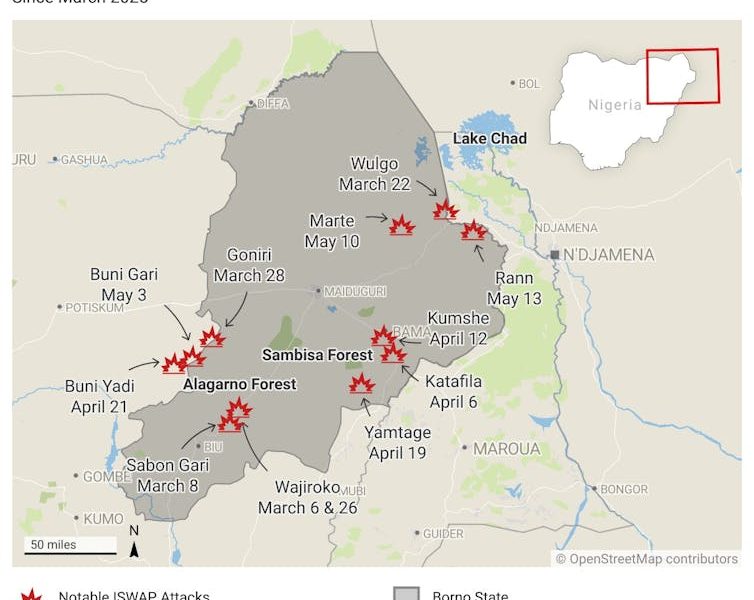

The group has overrun security positions in Borno state, a region of north-east Nigeria, a dozen times in the past few months. Borno state has been the epicentre of a conflict between the Nigerian army and jihadist insurgents for 15 years. The UN Development Programme said in 2021 that the violence had killed more than 35,000 people there directly.

The latest offensive began in March with a string of attacks. This included an improvised explosive device planted underneath a commercial vehicle in Biu, a town in southern Borno state, which killed four people and injured four others.

Iswap then launched several more attacks the following month, including an operation on a Nigerian army barracks in Yamtage town. It claimed to have killed three soldiers. The group sustained its campaign into May, with the launch of one of its most sophisticated attacks in recent memory.

On May 12, suspected Iswap militants stormed the town of Marte, capturing several soldiers and forcing others to retreat. A coordinated dual strike on nearby Rann and Dikwa towns followed hours later. The insurgents now have a strong presence in Marte, which holds immense strategic value due to its access to Lake Chad smuggling corridors.

Iswap, which was originally formed in 2015 as an offshoot of Boko Haram and has around 5,000 fighters, appears to be adapting to the Nigerian army’s military strategy. Since 2019, the Nigerian army has consolidated its forces in a heavily fortified “super camp” in key towns and cities in the north-east, from which they can respond to reported insurgent activity.

However, Iswap militants have launched several attacks on some of these camps by using tactics such as nighttime raids. They have also targeted bridges and roads between the camps, as well as launching attacks on nearby positions as a diversion, to prevent reinforcements from reaching targeted bases.

Iswap has been carrying out a sustained offensive against the Nigerian army since March.

Institute for the Study of War

There are several factors that could explain Iswap’s resurgence. The first is that there have been strategic shifts on the ground, including a lull in fighting between Iswap and rival faction Boko Haram over territorial control.

Niger also withdrew its troops from the region’s counter-terrorism joint task force in March. The security vacuum created by this withdrawal may have further emboldened Iswap to carry out its offensive.

Nigeria and Niger share a long border, so the reduction in military patrols could have led to an increase in the number of weapons and militants supplied to Iswap from its regional network.

The second factor is that the authorities have relied too heavily on responding militarily to the threat posed by Boko Haram and Iswap. The joint task force has launched several major offensives against the two groups in recent years, helping to contain the insurgency. This has led to the return of refugees to some parts of the Lake Chad basin.

But the reliance on military offensives has only prolonged the conflict, allowing the terrorist groups to evolve. Iswap, for instance, is now using sophisticated weaponry including armed drones to stage attacks.

A recent assault on a military base in Wajikoro in north-eastern Borno state began with the use of four drones armed with grenades. The group had previously used drones almost entirely to conduct surveillance and gather intelligence.

Dismantling and ultimately defeating terrorist groups such as Iswap in the region will require addressing the root causes and drivers of insecurity. These include poverty, inequality, unemployment, poor governance and weak institutions. Poverty rates in north-eastern Nigeria are estimated at over 70%, almost double the rate in the rest of the country.

The third factor that could explain Iswap’s resurgence is that it has been using technology effectively to expand its appeal, particularly among young people, and drive recruitment.

It has intensified its presence on social media, using TikTok to post videos justifying killings, lecture young audiences about extremist ideologies and spreading jihadist propaganda. It is also deploying AI tools to edit videos and written communications.

At the same time, it is making use of new satellite-based internet services such as Starlink to record footage of prayers and sermons. Starlink launched in 2019 with the aim of providing high-speed broadband internet to people all over the world, especially in remote areas.

Another factor is that Iswap has expanded its sources of funding. The group collects tax revenue from local populations in areas where it has a strong presence, with farmers in some parts of Borno state reportedly paying about ₦10,000 (£5) per hectare.

But Iswap is also allegedly tapping into Nigeria’s fast-growing cryptocurrency markets and earns considerable revenue from black market operations. The groups’s ability to rely on multiple revenue sources has ensured its supremacy over other terrorist groups in the region, while enabling it to plan and execute more sophisticated attacks.

The growing strength of Iswap will undoubtedly have dire consequences for peace and security in Nigeria. It could help coordinate Islamic State’s activity in west Africa, giving it a stronger foothold in the region.

Emphasis should be placed on addressing the root causes of the insurgency in Nigeria, as well as implementing tighter measures to constrain Iswap’s sources of funding.

Folahanmi Aina does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.