Rough sleeping to be decriminalised: what is the Vagrancy Act?

The Labour government has announced plans to scrap the laws associated with criminalising homelessness from spring 2026. This comes in the form of repealing the Vagrancy Act, which has made rough sleeping and begging illegal in England and Wales for 200 years.

Rough sleeping has increased 164% from when monitoring began in 2010. While repealing the act won’t end rough sleeping, decriminalisation is an important step to making sure the estimated 4,667 rough sleepers across England can access much needed support.

With less threat of hostile interactions with the police and incurring fines resulting in debts, there is a chance to instead focus on meeting their more immediate needs to help them exit homelessness.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

The Vagrancy Act 1824 was designed to address public order and so-called “undesirable” behaviours. Its full name is: An act for the punishment of idle and disorderly persons, and rogues and vagabonds, in England.

While homelessness as a whole is not made illegal by this act, it does criminalise behaviour associated with homelessness. This includes rough sleeping, loitering and begging.

However, as very few people rough sleep if they have another choice (and those choices are often also unappealing), the law does not act as a deterrent. In reality, giving people criminal records and potential debt worsens their chances of securing housing.

Over the years, parts of the act have been repealed, such as the offence of fortune telling. However, statutes covering “sleeping out” and begging are still in effect. Today, the Vagrancy Act gives police in England and Wales the power to issue fines of up to £1,000 and prosecute those caught begging or sleeping out.

In reality, the act has been used less and less over the years. However, the figures do not reflect how the law is used informally by the police to move people on and seize their possessions, including tents and sleeping bags.

It is not uncommon for old laws to be repealed as they become outdated. This announcement comes after years of campaigning from the homelessness sector and advocacy groups.

Organisations such as Crisis called the act “outdated” and “cruel”. Among other reasons, this is because the foundations of the legislation are degrading and overly punitive. In its earliest form, the 1547 Vagrancy Act authorised any able-bodied person who was not in employment to be branded with a “V” for “vagrant”.

Westminster initially voted in favour of repealing the Vagrancy Act in 2022. However, progress stalled while the former government considered replacement legislation.

At the same time, the Conservative government was considering making it a civil offence for charities to supply “nuisance” tents. And there were concerns that the last government’s criminal justice bill, which did not pass before the general election, would have allowed for homeless people to be arrested or fined for having “excessive odour”.

The current government has said it will replace the Vagrancy Act with legislation targeting organised begging by gangs and trespassing.

What difference will it make?

Homelessness charity Crisis called the announcement to repeal the Vagrancy Act a “monumental campaign win”.

However, neither the act, nor repealing it, addresses the real issues causing homelessness. Some key reasons that people become homeless are: family disputes, breakdown of relationships, domestic violence, poverty, unsuitable housing, addiction, long housing waiting lists and losing employment. By criminalising or fining people in these situations, they are less likely to find housing and exit homelessness.

Rough sleeping is already dangerous. Being visibly homeless increases the risk of becoming a victim of violence, in addition to the health concerns that come with exposure to all types of weather. With rough sleeping decriminalised, agencies will be better placed to offer lifesaving support, including giving out sleeping bags during winter months, without concern or threats of fines.

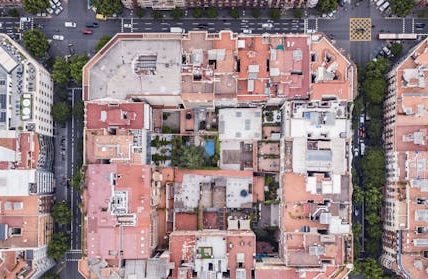

There are an estimated 4,667 rough sleepers across England.

Travers Lewis/Shutterstock

As well as immediate care, services also offer longer term interventions that address the root causes of rough sleeping. Evidence shows that providing support that focuses on what a person needs, such as help with trauma or addiction, is the most effective way for them to exit homelessness for good.

Repealing the act is also a positive step towards mending relations between the government, police and homeless people. For many generations, the focus has been on punishment rather than support. Moving our attention away from prosecuting will also help relieve a burden on the criminal justice system, freeing up already strained police and courts.

While the repeal is one important step to supporting homeless people and ending homelessness, it is only part of the solution. Rough sleeping is the most visible type of homelessness, but a much larger number of homeless people are hidden; people can live in temporary accommodation and shelters for years and others sofa surf with friends, family and strangers to stay off the streets.

Meanwhile, charities and local councils are supporting more people than ever on insecure and ever shrinking budgets. With an ongoing housing crisis, there are not enough suitable homes to place people in. Families living in hotels are at record high levels. Without responding to these issues, ending homelessness for good is unlikely.

Emily Wertans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.